Your browser does not support .avif images. Please view on a modern desktop browser, released after autumn 2021. No apologies for not supporting Microsoft’s rubbish. View this page on the desktop mit Google Chrome from version 82, Opera from version 71, Safari from version 16.1, oder even better Firefox from version 93.

Preliminary Remarks

India is so completely different that I hope this longish introduction will help. Those who have already been there can skip this section. The actual tour starts in Shimla.

Poverty is appalling, but you can’t help everyone. Personally, I've given beggars (never children) 30-50 Rs a day (more doesn’t seem sensible, since otherwise every passing foreigner would be treated as a cash cow), just to the first two people who asked in the morning. “Don’t look them in the eye” – meaning beggars, touts, etc. – otherwise you won’t get rid of them! It’s important to get into the habit of a “blank stare,” as rude as that may seem at first.

At some point, the heat, noise, dirt, constant cheating and stench(es), as well as the obnoxious natives, become too much. By “pushy,” I mean, for example, the twentieth shoeshine boy that day who offers to polish your sandals. In that case, a one or two-day “escape” helps: off to a “luxury” hotel for € 30-50, air conditioning on full blast, curtains closed and a good night’s sleep. One word of warning: when Indians adrvertise something as “international” or “world class” one can be sure it’s absolute crap in anybody else’s eye.

Delhi Belly: affects everyone, but usually only after 4-6 weeks in the country. A week of painful diarrhea, which is not relieved by medication. Immodium doesn’t help much – it tends to keep the bacteria in longer; if available, try homeopathic treatment (very common in India) with sulfur globules and charcoal tablets. Off to bed, black tea and a banana a day—that’s all you can get. Fanatical drinking of mineral water isn’t absolutely necessary. Every German camping store sells water purification drops. These and an unbreakable PET bottle (bring one from Germany; Adelholzener seems to be the most stable) are helpful. [Adelholzner is a German mineral water brand. Coke bottles are almost as sturdy.]

"Every man needs paper …” In India, one should never leave the house without a toilet roll. One meets, however, these “travellers” who have read in THE book (Lonely Planet† (Reading those guidebooks one also notices a general bias against using trains. Also wherever melons grow they are inevitably described as “wonderfully sweet” etc.) has caused more damage to Asia than tsunamis and earthquakes) how much more hygienic it is to wipe your bottom with your left hand while squatting and now preach this. Equally annoying are the English or American women, mostly in their twenties, who reproach you because two beers, on two consecutive evenings, will cost so many years of your life. They usually add, “I am vegetarian" - that’s fine with me, darling! Living a vegetarian lifestyle makes perfect sense in India; many packages are marked accordingly with a green square: there is no beef available, mutton and chicken are always tough and seeing how pigs live puts you off, just as seeing fly-covered pieces of meat left unrefrigerated in the market does - but please stop your self-righteous moralizing!

Manhole covers in India are mostly made of concrete, as iron ones are stolen for their metal content.

What did change since 1994?

- There are more public toilets in big cities, some with attendants are even tolerably well maintained.

- The public drinking water supply has been greatly expanded. Not only are there taps on train platforms (serving the surrounding neighborhood), but there are also more “baths” with hand pumps and ankle-high basins. It’s worth noting that Indians are physically very clean and almost all wash/bathe daily; unfortunately, they are not very respectful of their environment. Taboos regarding higher-caste Hindus require the use of disposable containers, unfortunately all too often made of non-degradable plastic, instead of the clay pots or leaves used in the past.

- The telephone network has been expanded (the days of having to queue at the post office for long-distance calls ended around 1985). Today, the probability of getting through on a landline is a good 95 % (even with a cell phone, you incur roaming charges between regions within India [abolished in 2018]). There are public telephones on every corner, i.e., booths with telephones on the table (signs: STD/ISD).

- I didn’t see any umbrella repairers on the side of the road (but that might have been due to the time of year).

- Lepers all seem to get free medication. At least the beggars who would shove their festering wounds under your nose have disappeared (personally, I can’t remember anything more disgusting than a rotting, open, stinking arm).

- The food on trains has gotten significantly worse. Previously, a conductor would come around, take orders and at the next station, a cable would be sent ahead and fresh food would be delivered on proper plates. Today, the dining cars serve warmed-up food from aluminum trays, like on airplanes.

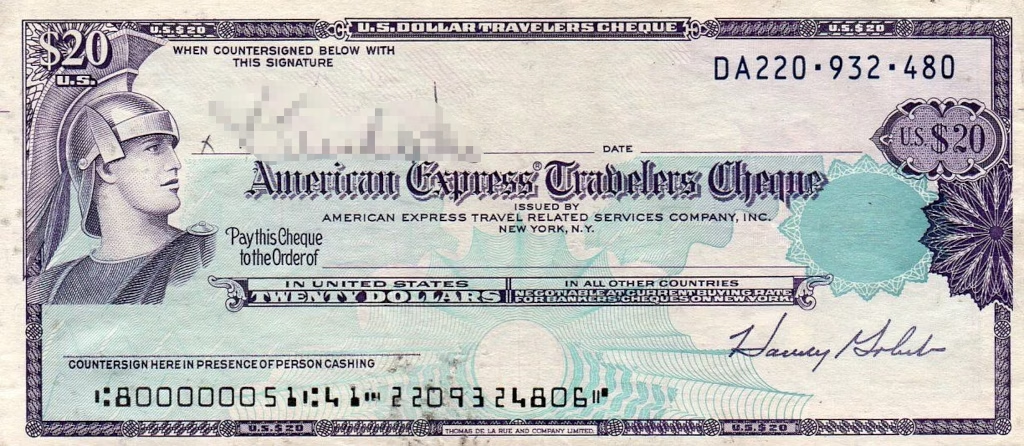

- The requirement to present official money exchange forms has been eliminated. The exchange rate for cash is almost the same in banks and on the street. Banks are really only needed for Traveller’s checks

. [Which no longer exist.]

. [Which no longer exist.]

Regarding “India travelogues,” be it books, photos or the internet, one problem in my opinion is that one cannot convey the olfactory experience to the reader (to put it plainly: the stench is sometimes indescribable).

Two days before departure, I started to have pain in my left ankle. “Well, it’s a little sore, it'll go away in a few days.” There was no time left for a doctor’s visit. First of all: Think again! Zwei Tage vor Abflug, begann ich Schmerzen im linken Knöchel zu haben. „Naja, leicht vertreten, das hört in ein paar Tagen schon wieder auf“ Zeit für einen Arztbesuch war nicht mehr. Vorneweg: Denkste!

Paperwork

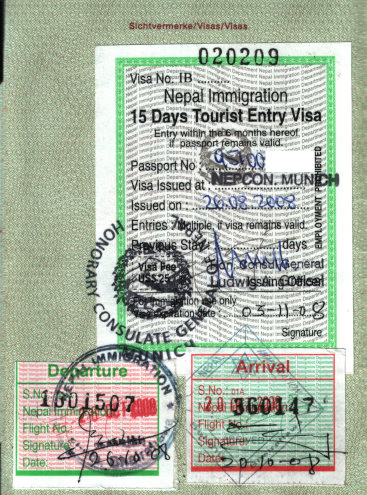

In Munich, there is an Indian consulate and an honorary consul of Nepal. This gentleman was [in 2008] a dentist with a private practice in a prime downtown location, which functioned as consulate on Tuesdays; the typical smell lingered. “Next please" is allowed to drop off the form, photo and payment in the consulting room and pick it up again on Thursday – „Mammi, Mammi, er hat gar nicht gebohrt!“ [This is a reference to the catch phrase of TV commercial for toothpaste in Germany of the early 1970s, meaning “the doc didn’t find any cavities.”] [The consul is Ludwig Greissl, who was one of the first climbers of Annapurna’s middle peak.]

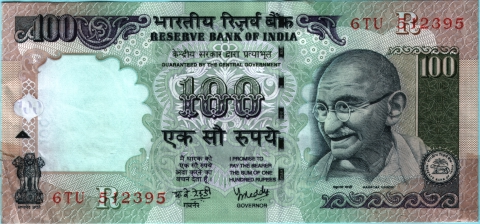

In India, there are still certain regions, mostly near the border (Assam, Andaman Islands), for which you need a permit in addition to the visa (€ 40 in 2008). Sikkim was of interest to me, but for some time now, the permit cost € 30 in Germany, whereas it’s free in India but cumbersome to get there. Fortunately, I knew from my previous visit that such applications, which are otherwise free of charge, are processed much faster by attaching colorful Gandhi portraits within the documentation. [The rules were relaxed or repealed in the early 2020s. However, for the areas near the border with China, you still have to book a (supervised) tour group.]

Something that will stay with travellers forever is the “C-Form,” the registration form for foreigners staying at hotels. It must be completed in triplicate; sometimes an entry in the guest book is sufficient. [As of 2021 it is available online] Besides the usual: name and address, they ask for the father’s name, passport number, place/date of issue, visa number, date of entry, where from?, where to? and for how long? During my first stay, I had a rubber stamp with my passport/visa details made for $ 2.

You should bring maps and sunscreen from Germany. In India, you'll occasionally need photocopies of the passport pages with your personal information and visa. You can get passport photos taken quite cheaply from a photographer there. Data protection and privacy are nonexistent. Be aware that the Indian government relies on total surveillance.1 Many internet cafes photocopy/scan your passport (!). One shop in Calcutta even asked for my fingerprint, so I left.

“Average residential area:" Slums along railway tracks, like here in Delhi, are common. These people pay “rent" to the local gang boss, who ensures that evictions from the community aren’t too frequent.

Trains and Buses

There’s a reasonably organized bus station in every larger town. Departures at the beginning of a route are reasonably punctual. “Deluxe” buses often even have panes in the windows. One shouldn’t look too closely at the vehicles if one has even a moderate European regarding vehicular safety. English is usually spoken at the counter and the destination is almost always written in western letters. It’s common practice to tie luggage to the roof, things rarely go missing; excessive suspicion isn’t warranted.

“Retiring room” combination toilet. One also squat on the extra-wide rim of the bowl.

For foreigners, travelling by train is probably the easiest and most frequently used option. On the broad-gauge railway, there are five classes, from first class air-conditioned to second unreserved (wooden bench class), which costs next to nothing (around € 2.80 for 600 km), but for which an infinite number of tickets are sold. A second-class sleeper with a reservation is usually sufficient, roughly equivalent to a European couchette. I avoid air-conditioned (A/C), as it is poorly maintained (as everything else in India) and rarely works properly and plastic-covered seats quickly get sticky when sweated on. The carriage doors are locked from the inside at night. Smoking compartments no longer exist, although smoking is still permitted between carriages in the lower classes (2008). It should be noted that the definition of a “super fast express” is a train that exceeds 55 km/h on average.

The Indian Rail Pass is not attractive in terms of price, unless you spend every night on a train. It doesn’t save you from queuing for reservations either. The quota system dates back to the good old days. Each long-distance train has a certain number of assigned seats for each station – no more can be sold initially. However, there are additional quotas for foreigners, women (sometimes in special compartments), civil servants, Liberation War fighters, etc. If you ask again shortly before departure, you might get lucky as the quoat seats are sold to the general public then. As computerized bookings are becoming more widespread, the quota system is no longer as important. A 20 Rs surcharge is charged for computerized tickets. There is a website where you can check the occupancy of long-distance trains. However, it didn’t work all that well in 2008 [nor 2013] (URL 2025 the design had been modernized.)

The timetable Trains at a Glance, available at many station kiosks, is still indispensable, if only because of its route map.

Since electrification has progressed, rooftop travel has been banned for obvious reasons. Why? Man Electrocutes Himself On Train - India).

The train carriage windows have bars to prevent boarding and disembarking. This, however, makes the carriages death traps in the event of an accident. Of the four toilets in a carriage, at least one in the better classes is “western.” Unlike in 1994, they are now even cleaned at certain stations, sometimes with Kärcher high-pressure cleaners.

A truly practical innovation are the “retiring rooms.” These are rooms or dorm beds at all major train stations that you can book until your connecting train arrives. Laundry facilities are usually available.

Luggage storage usually requires that the bag or suitcase be locked. For backpacks, one can buy a one-meter chain and a padlock cheaply in India. Many Indians also lock their suitcases in the compartment with these.

Shimla

Note: in 2025 one Euro was worth only 70 % of what it had been in 2008. Insofar Euro prices are quoted below they should be multiplied by 1.42 to adjust for inflation.

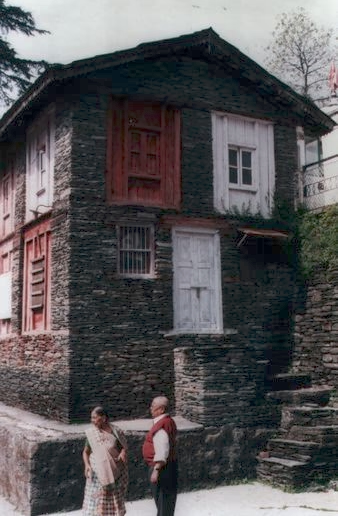

Shimla was the summer capital of British India. Because the plains become unbearably hot in spring, the entire administration, including all its files, were moved twice a year. Up in March and back down at the end of October (until 1911 from Calcutta, then from New Delhi). There were similar “hill stations” for the provincial administrations, such as Darjeeling.

On the upper floor of New Delhi Station, there is a special counter with an air-conditioned lounge for foreigners. However, from the Kalka interchange station, I was only offered second-class tickets for the Shimla Toy Train2). What the ticket clerk didn’t tell me was that the annual festival was coming up in Shimla and everything was fully booked. Second class was bearable up until the interchange station. I had actually expected there to be a first-class seat available, but that wasn’t the case; the conductor showed me to the overcrowded second-class carriage. I simply remained standing in first class for the six hours. The conductor (tickets for reserved seats are only checked once) and I squinted at each other several times when he passed the carriage during intermediate stops on the platform.

When I arrived after dark, there were no accommodations available because of the festival. I had to take a four-bed room for 1,100 rupees. I ended up arguing with the guy at reception because I was too stupid to tell the difference between 100- and 1,000-rupee notes. A sign of exhaustion.

The next morning, I strolled through this wonderfully relaxed place. I hadn’t eaten anything for three days since my flight from Frankfurt due to a lack of appetite. I suddenly felt dizzy with hunger – the 500 meters to the nearest street stall, where they sold fried toast with egg, was extremely difficult. My next stupid move was to give a turbaned beggar—or so I thought—in front of the hotel my entire “begging quota of the day,” 50 Rs. In fact, the man was a sadhu (“saint”), whose blessings were offered by placing a coin in a vessel filled with oil. That same afternoon, his gaze met mine, full of contempt...

The “traditional costume parade” that took place later, for which several artists had traveled, offered everything you could wish for in India: drummers, elephants, camels, sword dancing and everything very loud and colorful.

Shimla is the birthplace of the Nehru jacket“  the sleeveless waistcoat with a stand-up collar that Jawaharlal Nehru practically always wore. They are correctly called Shimla jackets (or achkan or sherwani ) and the woolen version, costing 120-150 Rs, is a worthwhile investment for cool evenings.

the sleeveless waistcoat with a stand-up collar that Jawaharlal Nehru practically always wore. They are correctly called Shimla jackets (or achkan or sherwani ) and the woolen version, costing 120-150 Rs, is a worthwhile investment for cool evenings.

In Shimla bin ich dann in den ersten Neubuchladen hinein, stehe vor dem Regal mit Biographien und – auf Augenhöhe – strahlt ER mich an: Zu haben für 2,50 € eine Raubkopie der englischen Übersetzung von Mein Kampf, inklusive Führerbild vorne und am Rücken!

Weiter ging’s per Nachtbus nach Westen.

Dharamsala (MacLeod Ganj)

Dharamsala is the Dalai Lama’s place of exile. The district, largely inhabited by Tibetans, is called MacLeod Ganj. It lies 400 meters above Dharamsala. The taxi takes us up past a barracks (“cantonment”) on a steep road that I wouldn’t dare drive. I was very glad to take the night bus down because it was dark. At the end of October, the surrounding mountain peaks were already dusted with snow.

In Dharamsala the Tibetans are much more relaxed compared to the Hindus. One gets hassled a less frequently. The infrastructure is very much geared towards Western guests. One advantage of this is that decent strong black coffee is available.

Among the tourists, numerous middle-aged “feminists” stand out, who are clearly keeping a handsome Tibetan boy-lover twenty years their junior. Then there’s the usual Lonely Planet-toting crowd of female backpackers in their mid-20s who wouldn’t dare step onto the subway in their London suburb, unless they were holding their mum’s hand. These types can be avoided, though. More pleasant conversation partners are the people sent by numerous Western development aid organizations who are trying to learn the language and culture. His Holiness wasn’t in town. The crowds at the temple, which adjoins his residence (discreetly but closely guarded by Indian soldiers), were limited. This Tibetan-style temple is freely accessible during the day but offers little architecturally. Inside, there’s a souvenir and book shop./p>

A Miss Tibet pageant took place at the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts (TIPA) – two contestants  competed. This event, held in such a venue, was not met with unanimous approval; conservative moralists called it “aping Western culture.”

competed. This event, held in such a venue, was not met with unanimous approval; conservative moralists called it “aping Western culture.”

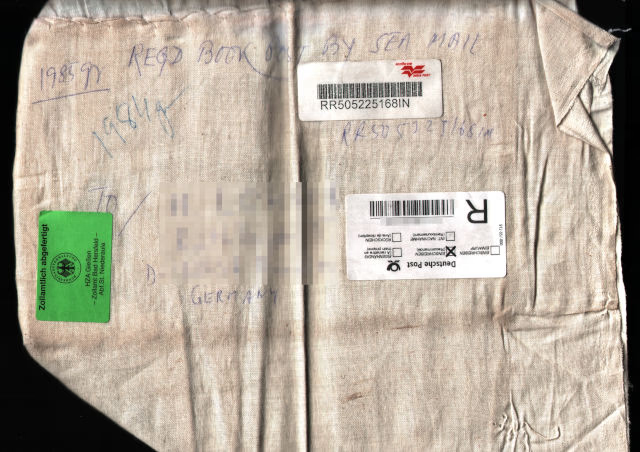

Bookworm bookstore is really well-stocked. Staff at the Dharamsala post office is also very professional due to the large number of parcels sent abroad. Note: Parcels must be sewn in India.

Looking like this after delivery in Germany. There’s a tailor outside every post office who will do this according to regulations for 20-80 rupees, depending on the size. Otherwise, send everything by registered mail, so no stamps are affixed. Counter staff are happy to peel them off and resell them and the letter ends up in the trash (the postage for a 100 g airmail letter can easily be worth a day’s wages). Alternatively, you can insist on having the stamp canceled in front of you.

In the lower part of the town, i. e., Dharamsala proper, is the Himachal Pradesh Local History Museum, with a modest but not entirely uninteresting exhibition. Admission is Rs. 2 for Indians and Rs. 50 for foreigners. If you have a few hours at the nearby bus station, a visit of one or two hours is worthwhile; there’s no need to drive there.

A night bus took me to Dehra Dun, where a British concentration camp was located during World War II. There, “enemy aliens,” primarily Germans and Italians, were interned separately in two subcamps: pro-Nazi and anti-Nazi. Ironically, the latter also housed numerous Jews with German passports. From this camp, the mountaineers and SS members Heinrich Harrer and Peter Aufschnaitter escaped to Tibet. There’s nothing left to see.

The place is still famous for the Doon School, founded in 1929. This was the first modern boarding school for Indians in India, modeled on a British public school for elite education. Numerous later leading politicians of independent India were educated here. Those who have published memoirs have one thing in common: they remember the boarding school primarily for its lousy food.

Then I continued by train via Barreilly to Lucknow. I skipped the nearby Hindu pilgrimage sites of Rishikesh (known to older people through the Beatles) and Haridwar. When there’s no pilgrimage festival, there’s not much to see there other than the Ganges. At 1.84 m (6'1"), weighing two hundred pounds and having had a knee surgery, I don’t have the flexibility for yoga. I prefer a relaxed, uncontorted Buddhist meditation.

Lucknow, then Gorakhpur

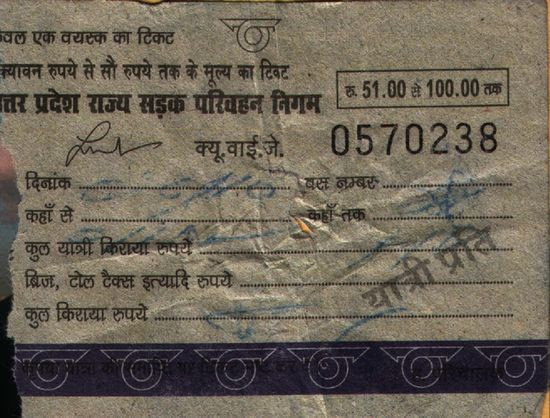

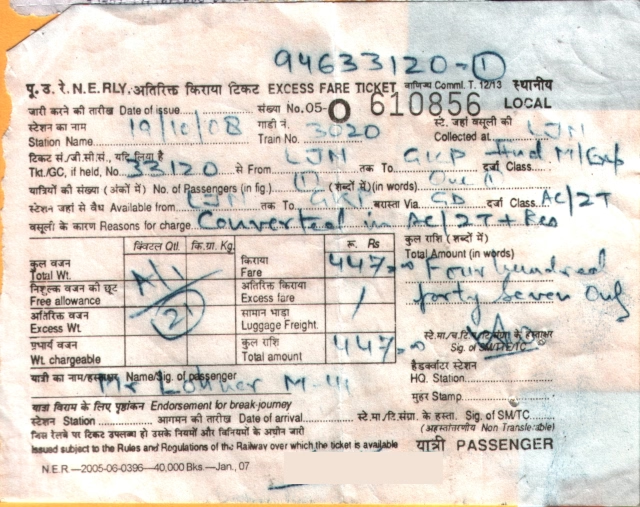

Train ticket, upgrade to a higher class.

The train (2nd class reserved seat) was bearable and arrived in the morning. Lucknow was the long-besieged center of English resistance during the Sepoy Revolt of 1857. Colonial literature is replete with stories of British heroism.

In my opinion, Lucknow is the essence of the worst that India’s “Hindi Belt” has to offer. Noise, dirt and smog (the tuk-tuks still run on two-stroke gasoline, not natural gas like elsewhere), as well as extremely pushy hasslers. On top of that, my foot was hurting terribly; a bandage I’d bought in Dharamsala hadn’t helped. (It wasn’t until after my return that I realized I should have had surgery. But it was too late, so I spent four months on crutches and another eleven months in pain. But at least the orthopedic surgeon back home had a kind remark after his first examination: “Well, I can assure you of one thing: you don’t have bone cancer.” Thanks! I nneded that. A colleague with a bettter “bedside manner” two streets away took over the rest of my treatment.)

So I booked myself into the second hotel near the train station (my nose refused to go to the first one) for 300 Rs. per 24 hours. In front of the hotel, a dog had been run over, its entrails scattered all over the street. It lay there until late into the night.

My only pleasant experience in Lucknow was the Botanical Garden. I arrived by taxi at a side gate around 11 a.m. The guard wouldn’t let me in, as they're only open from 6 to 9 a.m. Around the corner from the main entrance, an officer (even ordinary guards wear military uniforms; this one had two gold stars) phoned the director of the institute, who let me in: “Welcome, you are a guest in our country.” The garden itself had little to offer.

I had only stopped in Lucknow to book a connection to Gorakhpur (towards Nepal). Unfortunately, like in many Indian cities, the foreigners' reservation desk is not in the train station, but in the city. Moreover, the peak travel season around Diwali was approaching. Therefore, only a “second unreserved” ticket was available – 600 km for just under € 3. The scheduled departure would have been at 3 a.m., but I arrived at the station at midnight. Sometime in the night, I found a rebooking desk where I got a “second class a/c sleeper" seat for an additional € 10.

One can enhance the “genuine India” experience the day after Diwali in the villages of Gumatapura, in Karnataka or Thalavadi village of Erode district in Tamil Nadu. Here the Gorehabba festival is held. Men spend the day throwing cow shit at each other.

The Enfield Bullet, the wet dream of countless bikers. An unmodified licensed replica of an English motorcycle (the 500 cc version has a good 25 hp and is a classic long-stroke engine). Exporting it to Europe privately only makes sense if you buy the export version; the bikes built for the Indian market rust apart after the second winter.

By now, the train was listed as being 3½ hours late. Trains in India always run in pairs: “up" and “down” with a specific name. Unfortunately, the platform on my train had been swapped, but both trains of that day’s pair arrived at almost the same time. So I boarded the train, found my compartment, bed made and everything. A conductor then woke me, mumbled something and left. Later, I spoke with a first lieutenant who was on his way to a new post. I didn’t realize that the place he mentioned was the other final destination of the route. For a member of a repressive state agency, the man was extremely well-educated and pleasant.

Shortly before 2 p.m. we reached our destination—unfortunately not Gorakhpur—and it soon dawned on me that I’d taken the wrong turn. The train was due to leave at 10 p.m., so we walked a hundred meters down the road (damn foot pain!) up a hill to the reservation office. “Sorry, sir. We close at 2 p.m. on Saturdays.” It was 5 minutes past 2 – this is India! Since the place was computerized, there was no chance of getting a decent ticket for a baksheesh. Then followed an 18-hour journey in the second-class luggage compartment. The carriage was packed. Now, high-caste Hindus are afraid of contaminating themselves by touching an unbeliever, which helped. Only one young Muslim squeezed in with me. I didn’t dare climbing down to pee; the space would have been mercilessly taken.

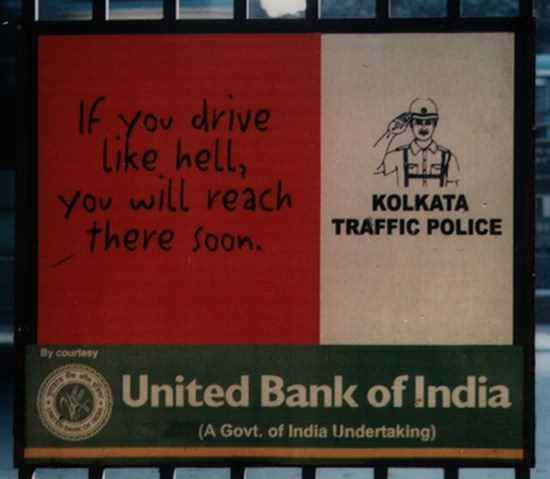

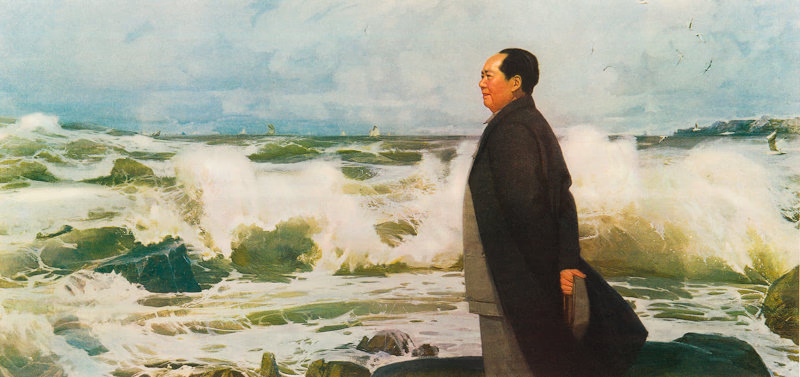

A different sign read: “Government Service is Service to the People.” in Inida this is taken about as seriously as in government offices in China where they pretend to “to serve the people” (為人民服務 Wéi rénmín fúwù. Mao Tse-tung; Serve the people (Sept. 8, 1944), Peking, Nov. 1965. – a euphemism for “we are a bunch of bludgers here."Incredible India.

Nepal

Lumbini (Buddha’s birth place)

Sagauli, a border town

Finally arriving in Gorakhpur, I continued relatively quickly by bus to the border town of Sagauli. The Indian side can be described as chaotic. However, the atmosphere is friendly. Even a bicycle rickshaw is too slow to get to the border, so awful is the traffic on the one main road with countless trucks trying to cross.

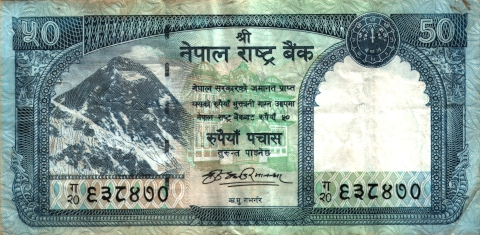

Locals cross back and forth at random, unchecked; there’s no barrier. Somewhere to the right, between a few shops, is the Indian check-out point, then a small hut for Nepal. I was very glad I already had my visa; you could get one at the border, but only for US$ 20 in cash (no rupees), a photo, etc. The travellers in front of me were annoyed by the hour-long process. On the Nepalese side, trucks were backed up for almost two kilometers. It was evening already.

The only accommodations in town are an expensive hotel and a guest house, but that was the classic dump. Peepholes in the walls, plastic buckets under a dripping sink, bedbugs (or god knows what else) in the mattress. Antique bedsheets that had never come in contact with Persil. On the roof, a terrace with a restaurant, but the kitchen won’t open with only three guests staying. So off to the street stalls, where I ate waterbuffalo kebab for the first time. The travelers from the border showed up too. We then had a pleasant evening on the roof terrace with a few cold beers and the bugs in the mattress then had a nice supper sucking on me.

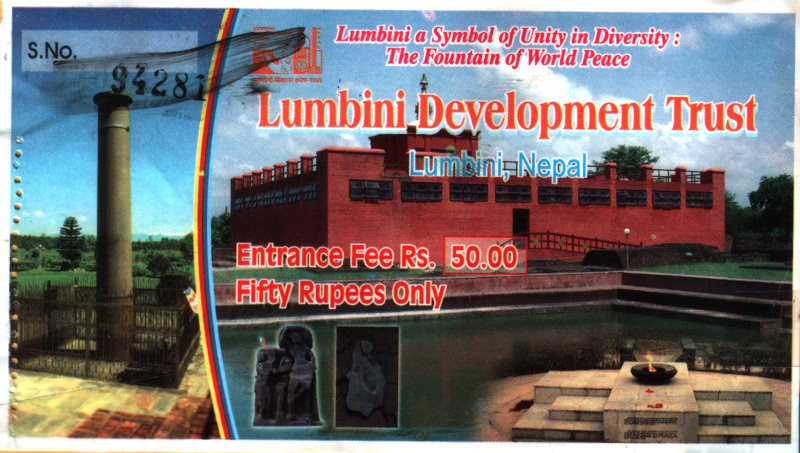

The next morning, I was the only one who wanted to go to Lumbini. The "travel agency" on the ground floor offered to rent a car for $ 20. That was way too much for a 14-kilometer trip. So I took the public bus, changing once.

Lumbini

LKW-Fahren in Nepal.

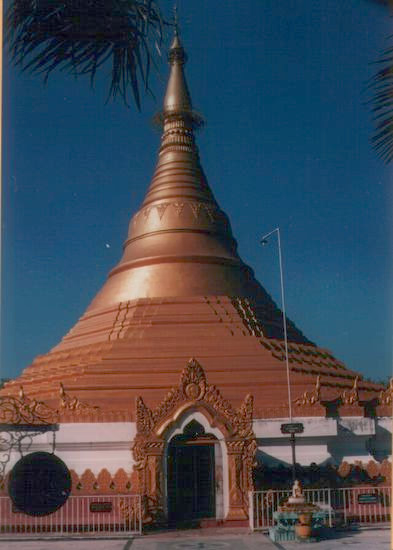

Lumbini, the legendary birthplace of Buddha, is divided into two parts. The surprisingly small village, consisting of barely 30 houses along the main drag and the huge Buddha Park, enclosed for miles by a cast-iron fence – both a nature reserve and a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1997. To get around, it’s a good idea to rent a bike – but before choosing, make sure you find one without a flat tire.

Breakfast in Lumbini is only available at one stall and they serve the same every day: “Channa with Puri,” a kind of chickpea curry soup with greasy flat bread. They also serve different food there in the afternoon. By then the flies were so numerous that I was glad to go elsewhere.

After weeks in India, the park is almost paradisical and quiet. Apart from monks and a few workers, no one is allowed to live there (theoretically). In recent decades, widely believers from various Buddhist countries have built their own temples, all of which are worth seeing.4 Some of them offer accommodation, but I preferred a guesthouse in the village. One should allow three full days to explore. Especially early in the morning the temples in the complex are exceptionally quiet and beautiful. Even the tour groups, mostly from China, who arrive by the busload, disperse throughout the area.

The main attraction is of course Buddha’s birthplace, in a hall with a “footprint,” a small museum, a Bodhi tree and the Ashoka pillar to the side. It has been very nicely renovated. Photography permits costs extra. On the way to the main entrance, a local woman has trained her six-year-old son to beg passersby with a phrase close to “their Buddhism.” For Europeans, “om mani padme um,” something different for Chinese and in Sanskrit for Indians.

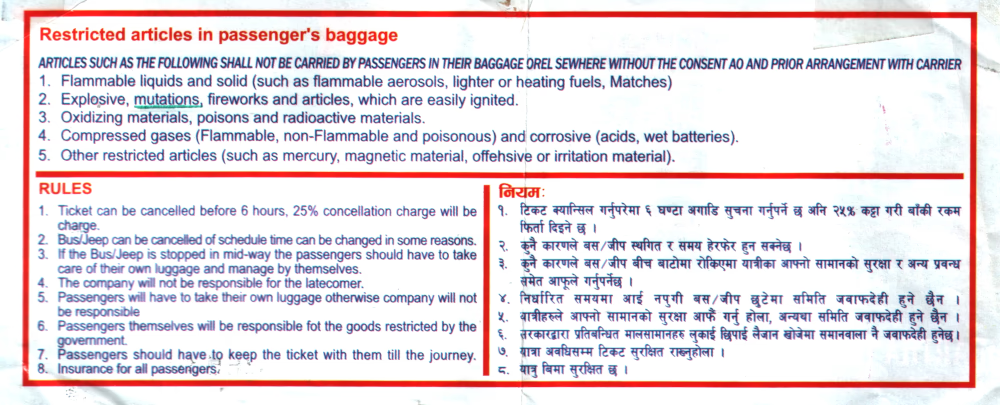

I then booked a VIP bus ride (a 9-seater Japanese minibus) to Kathmandu at the travel agency (see picture for conditions of carriage). While the lady was issuing me the ticket, what was probably the biggest rat I've ever seen ran along the cable hanging from the ceiling. The saleswoman was not surprised.

Kathmandu

“Truth in advertising.”

The journey through the foothills into the Himalayas leads up through spectacularly steep gorges along a riverbed. On the way to the Kathmandu plateau, there are a few rest stops where you can buy things like smoked fish from the river, honey, or dried frogs on sticks. In the minibus with me was a very friendly Chinese woman from Sian who spoke very good English. (Unmarried, as she emphasized several times). When she later rushed out of one of the rest houses and offered me an apple, the “Eve” analogy became a bit too much for me.

I was dropped off somewhere on the southern outskirts of Kathmandu, so I took a taxi to the only place I knew – “Freak Street.” Of course, there’s little left of it, but it’s centrally located. In the days that followed, I bought a beautiful hand-knitted sweater there. There are also travel agencies specializing in foreigners.

Anyone travelling to Kathmandu should get a city map at home—there are no street names, so you're quickly lost—because usable maps are rare on the subcontinent. I found “Kathmandu & Pathan City, 1:15000” from the Himalayan Map House (ISBN 99933-23-55-1) helpful.

In Thamel district, I found the Lansisha Guest House, a 3-star hotel by local standards, but at $ 5 for a double room, it was almost too cheap for the quality offered. Hot water, as is often the case on the subcontinent, was only available on request, delivered in bucket by room service.

The entire Durbar Square („Most of the structures in Kathmandu Durbar Square date from the 16th and 17th centuries, with a section dating back to the 12th century. The central feature of the square is the famous Hanuman Dhoka Palace complex. This magnificent palace was built in honour of the monkey god Hanuman and features a statue of the deity at the main entrance. Hanuman Dhoka Palace served as the residence of Nepal’s kings until 1800. It was furthermore the meeting place for important administrators. Numerous ceremonies were held here. The Nepalese palace is an impressive structure with ornate, carved wooden windows and panels. Visitors to the palace are welcome to explore the Mahendra Museum and the Tribhuvan Memorial Museum.”) with its pagodas and intricately carved walls, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Checkpoints have been set up at some locations (approx. 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.) that charge foreigners 200 NRs (€ 2.05). I have nothing against the entrance fee, especially if it truly serves preservation, but having to pay 200 NRs every time just to take the direct route to my hotel or the market became a bit tiresome – but it’s easy to find the shortcuts. [By 2020 the fee has been increased to 1000 NRs. – “highway robbery.”] The square itself isn’t a museum, but rather the city center, around which life is bustling. There are a few rooftop restaurants around the square (dining is not mandatory) where you can enjoy the sunset over the city.

Sunset over Kathmandu. Thanks to the daily power outage every evening, no street lighting polluting the view.

Biggest fuss in the local media during my stay at the end of October 2008 was the fact that the king, deposed in 2006, hadn’t paid his electricity bill upon his recent departure from the palace. Given the power outages that occurred several times a day — you could bet on the one at sunset, down to the minute — I wouldn’t have paid either.

A brief note on the deposed royal family: In Nepal (2003 GDP: US$ 240), freedom fighters inspired by the ideology of the Great Helmsman  had been aktiv since 1995. During the following decade, there were an estimated 11,500 violent deaths. After many years, the “communists” achieved participation in government through negotiations in 2006, after King Gyanendra (reigned from 2001, also head of government from 2005) resigned. Following the death of Birendra, who was only moderately popular at best numerous members of the dynasty were massacred by Prince Dipendra. He marched into a family dinner with a sub-machine gun and emptied a few magazines on the plates and into the diners. Gyanendra succeeded as ruler. He was unpopular from the start; on February 1, 2005, he declared a state of emergency and had hundreds of politically active Nepalis arrested. Since 2008, reactionary elements in politics and especially in the army, have remained strong.5

had been aktiv since 1995. During the following decade, there were an estimated 11,500 violent deaths. After many years, the “communists” achieved participation in government through negotiations in 2006, after King Gyanendra (reigned from 2001, also head of government from 2005) resigned. Following the death of Birendra, who was only moderately popular at best numerous members of the dynasty were massacred by Prince Dipendra. He marched into a family dinner with a sub-machine gun and emptied a few magazines on the plates and into the diners. Gyanendra succeeded as ruler. He was unpopular from the start; on February 1, 2005, he declared a state of emergency and had hundreds of politically active Nepalis arrested. Since 2008, reactionary elements in politics and especially in the army, have remained strong.5

Given the condition of the roads in Kathmandu – all side streets are unpaved – a flashlight is essential. A local “specialty” is the way in which work on sewers is carried out. On day one, the sand/cement to be processed is dumped in a pile in the middle of a street. On days two or three, a trench is dug by hand. The pipes delivered in between are thrown somewhere on the road. Days or weeks later, the dirt is shoveled back into the trench but not compacted, creating a beautiful bumpy track. Luxuries like barriers are unnecessary; the work preferably takes place in three-meter-wide bazaar streets, where deliveries arrive by motorbike day and night and people trample down the freshly dug earth. (Perfect for an evening stroll, just as the daily power cut kicks in!)

Next, I wanted to cross Nepal eastward to enter India at Bagdogra and from there to Sikkim. I bought a “luxury” bus ticket for Rs. 4,200 at a travel agency in Durbar Square. The departure was scheduled for 5 a.m. from the new central Gangabu bus station. That’s 14 km north of the city center. Oh, you naive European!

Getting up at 3:30 a.m., it took 15 minutes to wake the sleeping receptionist so he could open the shutter to get out of my hotel. Another 20 minutes later, a tuk-tuk came along the completely deserted street. The receptionist helped me out – the driver knew when to make a killing: 300 Rs to the bus station. I arrived there at 4:25 a.m. Everything was new and beautiful! Everything was empty, less so. It was about 7° C, everything was closed. Apart from a friendly night watchman, nothing and noone anywhere. Later, a few well-fed rats appeared. The toilet opened at 6, followed by the tea wallah. The travel agency had told me who to ask at which counter. The gentleman in question arrived “according to schedule" (in his opinion) at 7 sharp, but was genuinely surprised when I held out my ticket. I wasn’t entirely sure why the bus wasn’t running. The monsoon probably washed away a bridge six weeks earlier, but the travel agency should have known that (they had called specifically). Maybe another bus would leave around three in the afternoon, but no one knew for sure and I’d have to buy a new ticket. “Fuck this!” – the next bus south to the Indian border was supposed to leave at eight.

Instead I bought a ticket and off I went (forget about the 4000 paid at the travel agency). It was five to eight – and again no bus. “This Nepal, never on time!” At around 8:45, then “get in here,” a minibus with no windows. They drove wildly through the city, the “conductor” hanging out the door constantly calling out the destination. Since this bus didn’t fill up, I was asked to change and then again later while the new bus was already moving along at walking pace and eventually we got on the “highway" heading south. At the first rest stop, I put my luggage on the roof so I could stretch my feet (as much as that’s possible for someone 1.84 m tall in a bus “made in Japan").

Back in the lowlands we halt at the end of a traffic jam. It should be noted that in Nepal there are no warning triangles; instead, a stone is simply placed on the road in front of an accident/breakdown site. A broken-down vehicle, of which there are many, is marked by branches stuck in the wheel arches. We passed more than one truck that had fallen into a ditch.

[Abbildung ähnlich] This was one of those (rare) total road closures. Later, it was reported that two people had died, including a child. Regardless, the highway was already closed about two kilometers before the accident site. We were standing on the road (I was the only foreigner). About a hundred meters behind us was a tourist minibus; I hobbled over and chatted with two nice English women of retirement age.

Then another bus arrived with something that I find seriously annoying in Asia – unfortunately it’s “typically German." All over East Asia, feral dogs live as “mangy street dogs." In some cultures, dogs and pigs are considered equally unclean and any contact is avoided. In Chinese-influenced cultures, people keep lapdogs at best. In Korea, they make sure dogs are nice and fat  – before they go into the pot. Absolutely no one would dream of adopting a street dog and putting it on a leash. If you see something like that, you can bet the person is German or Swiss. (The more severe version is the pot-bellied, over-60-year-old on a beach in Thailand: leashed dog leash in one hand, hooker , who, in terms of age, could be his granddaughter on the other.) Now, a fellow of about 27, dressed in a dark blue pseudo-hippie uniform (his beard, about a week old and his messy hair indicated personal hygiene deficiencies), gets out of this overcrowded bus full of Nepalis, with a dog (rope, not leash, around its neck): “Heel!”6 (Asshole!!! With so much insensitivity towards the culture of foreign countries, it’s no wonder that tourists are just being ripped off … I won’t even get started on the miniskirt or singlet-wearing, braless blondes who scream “rape" after they got the attention they deserved. Anything else that comes to my mind is unprintable in the climate of “political correctness" that prevails in Germany today.)

– before they go into the pot. Absolutely no one would dream of adopting a street dog and putting it on a leash. If you see something like that, you can bet the person is German or Swiss. (The more severe version is the pot-bellied, over-60-year-old on a beach in Thailand: leashed dog leash in one hand, hooker , who, in terms of age, could be his granddaughter on the other.) Now, a fellow of about 27, dressed in a dark blue pseudo-hippie uniform (his beard, about a week old and his messy hair indicated personal hygiene deficiencies), gets out of this overcrowded bus full of Nepalis, with a dog (rope, not leash, around its neck): “Heel!”6 (Asshole!!! With so much insensitivity towards the culture of foreign countries, it’s no wonder that tourists are just being ripped off … I won’t even get started on the miniskirt or singlet-wearing, braless blondes who scream “rape" after they got the attention they deserved. Anything else that comes to my mind is unprintable in the climate of “political correctness" that prevails in Germany today.)

Suddenly I had to chase shouting loudly after my wild bus driver. He took advantage of the gap created by an ambulance to get closer to the beginning of the queue. The accident scene was cleared after two hours.

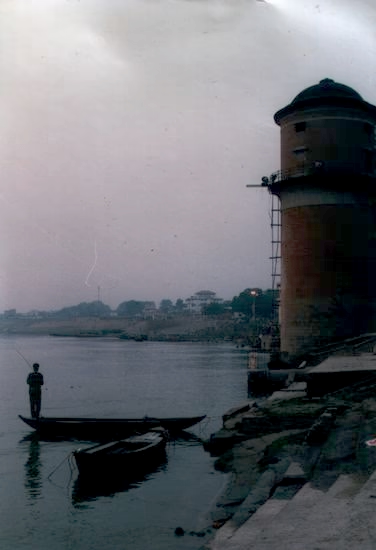

Another night on the Nepalese side of the border in the bug-ridden guesthouse from the inward journey, another well-seasoned water buffalo kebab (apparently not available in India) and off to Benares (Varanasi). First by bus to Gorakhpur, then a night train. A second-class sleeper, in which an Indian businessman is peeking around anxiously the next morning – his laptop had been stolen. Sure enough, an officer from the “Railway Protection Force” (railway police, armed with World War I Enfield .303 _-_AM.032056.avif) rifle, like those often carried by guards outside Indian banks) appears.

rifle, like those often carried by guards outside Indian banks) appears.

Varanasi and Sarnath

Varanasi (Benares)

I found accommodation quite by chance near Agoreshwar Ghat. An elderly Indian man was sitting in a shack on the side of the road, offering massages. They weren’t my thing, but he pointed out that there were rooms available in the house behind him. During peak season, 150 Rs for a three-bed room, which I occupied alone, was a good price. The owner, a Brahmin who was also religiously active, seemed less concerned with profit than with making a decent living for himself and his family. There was no service in the true sense of the word; people met more casually in the courtyard of the former colonial building (entrance and exit were through the massage parlor. If there were customers, which didn’t seem to be more than once a day, you might have to wait).

Sarnath

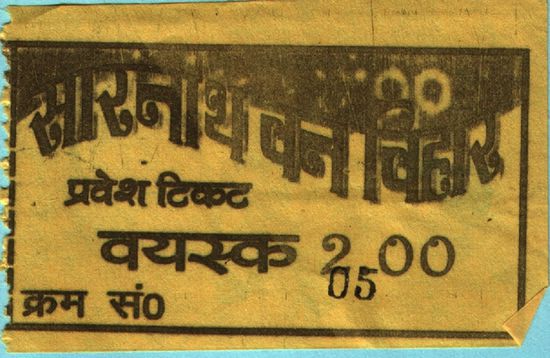

Sarnath is located about 20 kilometers northeast of Varanasi. While it can be reached by bus, a tuk-tuk ride might be easier.

There’s actually too much to see for just a day trip from Varanasi. The site, where Buddha is said to have delivered his first sermon, had been forgotten by the early 19th century before ist was rediscovered. The Maha Bodhi Society, which also built a well-maintained temple (सारनाथ मंदिर), played a key role in its renaissance .

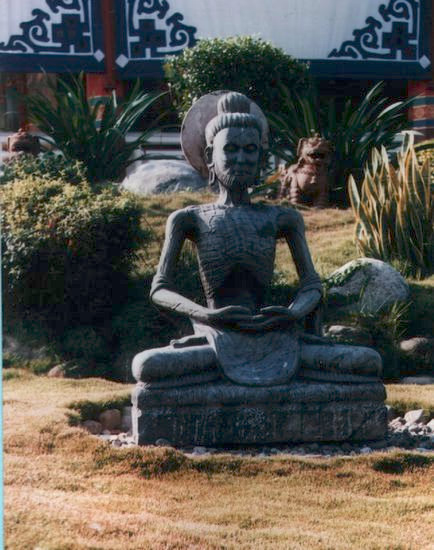

The grounds surrounding the temple are recreated with the stages of Buddha’s life, partly with statues like the one shown, partly with mannequins and naive murals. Very simple, almost primitive by European standards.

The temple is one of those where there are “official shoe-turners” soliciting baksheesh. The grounds are well-maintained. The lady at the book stand inside was helpful. Near the temple, a “Deer Park” has been established, which is considered a model for the one in Nara, Japan. There’s also a small, pleasant zoo that most visitors seem to overlook.

Diwali Festivals

Diwali, the Festival of Lights, is one of the most important festivals in the Hindu calendar. It lasts several days, involves fireworks and a generally high spirits celebration. Many Indians return home to their families weeks before.

I was in Varanasi on the final day, its climax, but felt not well enough to even leave my room. I supposes I missed something …

Trying to buy a ticket at the special ticket counter using the foreigner quota turned out to a waste of two hours. A pleasant conversation with a French woman and her 19-year-old daughter who were also waiting shortened the time. At the regular ticket counter, I was able to get a 2nd class sleeper ticket without any problems and within 20 minutes.

A lasting impression left an Indian man who sat down next to me at lunch – he wanted to try out his English. He was an “engineer” with a college education. The translation “graduate” would be incorrect here. For one thing, a college in India is not a university, but a secondary school for 14-18 year olds. These are more like a vocational preparatory (technical) schools. He was apparently a skilled machine operator – which is already a solid training there. We talked at length about the education systems in India and Europe. He was completely astonished when I mentioned that if I wouldn’t send my son to school, ultimately I might get sent to prison.

Education in India is still a privilege; secondary education (from 7th grade onwards) is usually privately organized and subject to fees. A € 50 tuition per semester on a monthly salary of Rs. 6,000 (approximately € 100) can be a huge burden. There are entrance exams for tertiary education, which are often very difficult. The literacy rate is highest at 94 % in the southern state of Kerala, which was long ruled of communists state governments. Bihar, the region between Varanasi and Calcutta, is the most backward state; it was here that the British first began their colonial exploitation ("drain” and “permanent settlement”), from which the region has not yet recovered.

Bodhgayā – a place of enlightenment?

Mahābodhi Temple

Yet Brahmans rule Benares still,

Buddh-Gaya’s ruins pit the hill,

And beef-fed zealots threaten ill

A tourist-show, a legend told,

A rusting bulk of bronze and gold,

So much and scarce so much, ye hold

Bodhgayā is traditionally considered the place where Buddha is said to have achieved enlightenment. A frequently remodelled Hindu-style Mahabodhi temple has existed there since at least the 4th century BCE. From the late 19th century onward, there was a dispute between the Hindu Mahant (religious administrator) who controlled this lucrative pilgrimage site and Buddhist groups (from Ceylon) who demanded a say in its management. Since 1949, the temple has been owned by a Buddhist foundation.

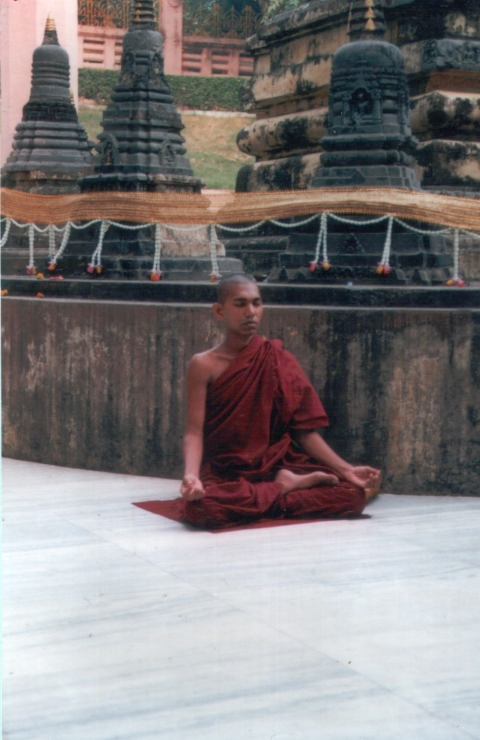

Within the walled temple, which is free to enter (one must leave shoes at the entrance – and given a numbered token), there is a well-stocked bookstore. Numerous Tibetan monks have set up their wooden benches. You can watch them performing their countless prostrations. I'm not sure if they also sleep there.

The complex is very well maintained by Indian standards, with flowerbeds surrounding the numerous stupas. The terraces and lawns surrounding the “Muchalinda Pond” (an artificial lake) are used by numerous meditators. The immediate temple grounds are crowded throughout the day, although even the otherwise noisy Chinese tour groups keep a low profile.

The current Bodhi tree was grown from a cutting brought from Ceylon. The one there, in turn, is said to have originated from a cutting brought there by Ashoka’s brother or son in the 3rd century BCE.

The lower branches are trimmed so that they cannot be reached by hand; whenever a leaf falls, a pilgrim will be found taking.

Outside the temple, one can clearly observe the locals’ business acumen. There is an exceptionally lively pilgrim market, catering to both Indian and Westerners. Rosaries, Buddha statues, “meditation music" CDs at full blast, snow globes (!), etc., ad nauseam.

Annoyances

Unfortunately, due to the large number of tourists, the beggars in Bodhgaya are extremely pushy. The children trained to beg (which is unfortunate in itself) are particularly annoying. Few European women can resist these goggle-eyed youngsters.

On the second day, as I was walking from the temple to my hotel, I had to rescue a 20-year-old Lithuanian woman who had made the mistake of taking a 20-rupee note out of her wallet. She was so surrounded by children that she couldn’t take another step and, on the other hand, didn’t know who to give the note to. She sat in the dining room with me in the hotel, bursting into tears at first, until the kids lifted the siege after 45 minutes and she dared to go home. Two days later, I saw her again, hiding on our stairs.

The fact that the locals are aware of the negative impact on their business is shown, for example, by the fact that paragraphs like “For a non-Indian it is almost impossible to walk 20 m in the streets without being accosted. Approaching the precincts of the Mahabodi-Temple one understands why Jesus threw the the money-lenders out of the Temple in Jerusalem. Riksha-Wallahs and the hordes of beggars, particularly the groups of children sent to beg instead of going to school, are much more persistent than in other places.” are repeatedly deleted from Wikitravel.

One evening during my four-day stay, I noticed a car parked in front of one of the better hotels. A pickup truck with a cabin of corrugated stainless steel panels (which must get terribly hot) and a license plate from Berne (Switzerland). I had already noticed that car in front of my bus on the way to Kathmandu. As I took a closer look, the Swiss owner was just getting out. We started chatting; his wife was sick in a hotel room with stomach problems and a fever. The two had driven through Siberia, China and the Karakoram Highway to Pakistan and from there to India and Nepal. It turned into a particularly pleasant evening when a professional American photographer living in Bangkok joined us. Since Bodhgayā, like so many Indian cities, is a “holy place” that is “dry” – meaning no alcohol is served publicly – my waiter on the floor, who kept us in beer, earned a nice extra that evening.

Other temples

Numerous believers have built temples in the traditions of their countries, particularly along the Domughan-Bodhgaya Road (there are also three banks for exchanging money). All of these are worth visiting, some even offer paid overnight accommodations for pilgrims.

The Bangladeshi Temple, a bubble-gum-pink building (still under construction in 2008) and the Japanese “Great Buddha” are striking, with the driveway besieged by countless postcard sellers. Early morning meditations are held in the adjacent Indosan Nippon temple. Especially within the temples, Bodhgayā offers numerous places of silence, which, along with the consistently well-maintained grounds, encourage you to linger.

The small archaeological museum is also worth a visit if you are interested in sculptures.

Calcutta

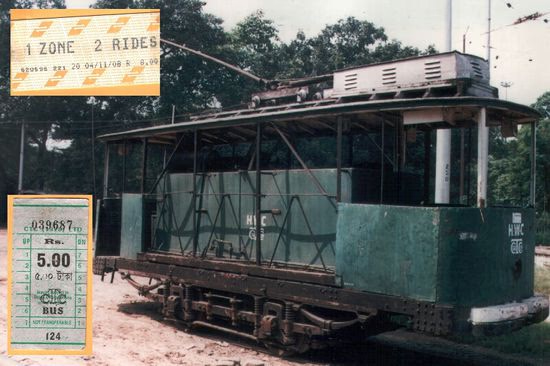

Calcutta tram. (Tickets for the Metro upper left, Bus below).

Nine years after its opening, the metro (subway) was already showing signs of decay typical of India; it is operated by a local company. In contrast, the Delhi metro, after eight years under French management, was in “European” condition. X-ray machines like those at airports are in place at the entrances in both cities, large luggage is not permitted.

Calcutta is the capital of Bengal. Today, the politically correct term is “Kolkata,” but for me, it is and remains a very delicate South Indian dessert.

Travel guides about the city are replete with stories of filth and harassment. The natives are somewhat darker-skinned and generally somewhat shorter than other Indians. The British colonial rulers considered Bengalis a effeminate race that was definitely not wanted in the army. The proportion of believers in the Koran is still comparatively high in West Bengal, but many emigrated to what was then East Pakistan (since 1971 Bangladesh).

A fellow, who I initially thought was a tout and therefore treated rather rudely, took me to a just about bearable hotel (300 Rs without TV and A/C) in the area behind the bazaar (near Esplanade).

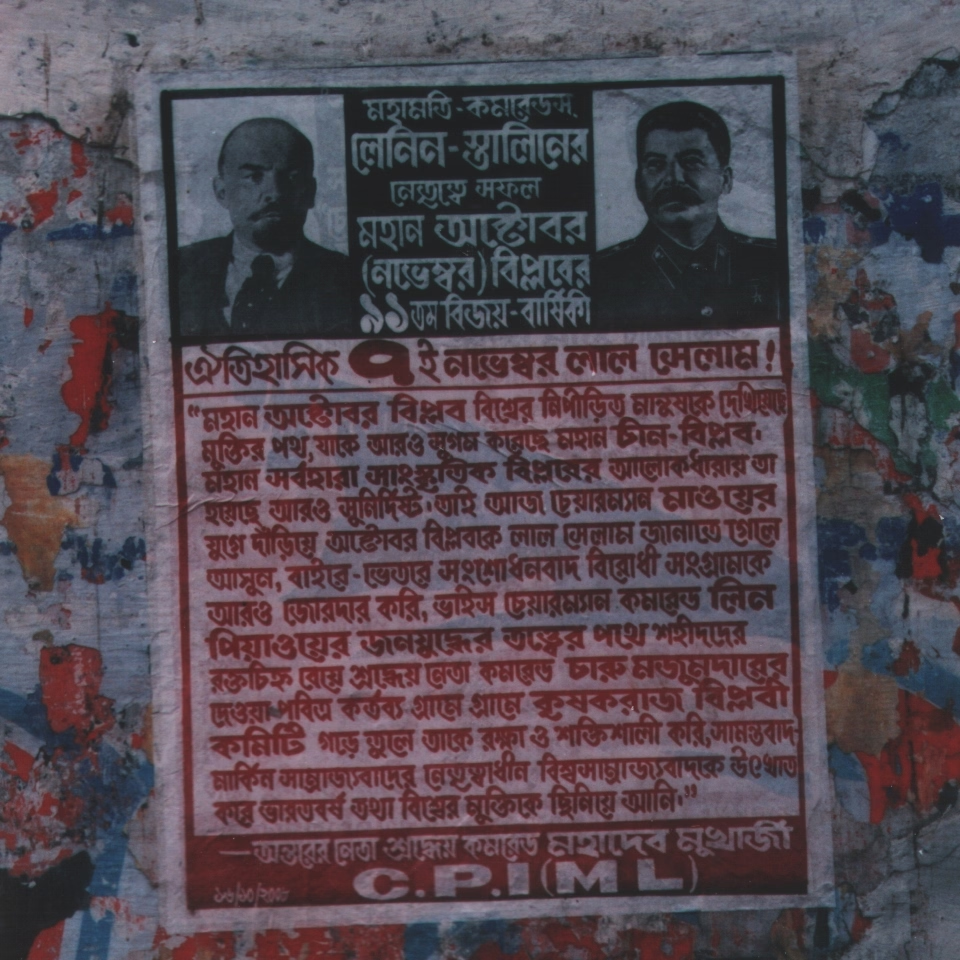

„Am deutschen Wesen soll die Welt genesen.“ [German political catchphrase from 1867, used by emperor Wilhelm II. 1907 “The world will be a better through the German spirit” – here used ironically with those two socialist greats Marx and Engels.]

The states of West Bengal and the city of Calcutta were governed by democratically elected communists for several decades (until 2012). Therefore, one finds:

- a functioning tram network

- a subway, which after nine years of operation showed typical Indian decay

- reasonably clean streets

- Taxi drivers who switch on their meters without hesitation (!)

- Traffic lights that not only work but are also observed

- every few days a “bandh,” i. e. strike with demonstration, often politically motivated

- In the main cash register of the electricity company there is a flower-wreathed portrait of Lenin, depicting him in the style of a Hindu god.

While still in Delhi, I had booked a flight to Pt. Blair in the Andaman Islands. While that’s actually an area where you need a permit, it was possible to get one upon arrival at the airport. Check-in was scheduled for 4:45 a.m. So, I took an Ambassador taxi from my hotel through deserted Calcutta to the airport, where — “this is India” — no flight was listed, it had been canceled. They didn’t want to rebook me either, but I could get my approximately $ 90 back from the travel agency in Delhi (!) (which worked and I even made some money from the exchange rate fluctuation).

Sudder Street

From the airport back to the hotel (Shams International behind Sudder Street); my room wasn’t cleaned by 9 a.m. anyway. “Just as well,” as the English say, because that afternoon the “Delhi belly” started in earnest. For the next three days, I crawled back and forth between bed and toilet. For another three days, I barely ate. In one week, I lost about eight kilos.

That caused some amusement (to me) when I went to pick up my custom-made suit. As I tried it on, the trousers were noticeably too big. The boss muttered something like, “What did that idiot measure?” He couldn’t believe you could lose that much weight in ten days. Barkat Ali && Bros. are certainly not the cheapest tailors (I had already bought 4.5 meters of “made in Italy” fabric for the jacket and two pairs of trousers in Kathmandu); the total came to € 150 and there was no haggling. The quality is good, but the service could be friendlier.

Mother Teresa

„Brüder zur Sonne, zur Freiheit!“ [Opening line of the the probably most sung song of the workers' movement in Germany. Translated from the Russian original: Smelo, tovarišči, v nogu!]

Worth mentioning is the Fairlawn Hotel – [renovated in 2010] similar to the Atlanta in Bangkok – an institution for those who aren’t afraid to enjoy a bit of colonial decadence every now and then. The garden restaurant was the place for a traditional sundowner (pink gin). I was still too sick for a beer (Kingfisher is especially drinkable in India). But a pot of black tea without milk in the cool garden was very pleasant in the evening.

There, I met a Frenchman who has been spending his vacations volunteering at Mother Teresa’s for years. He explained the situation to me a bit. The staff don’t collect “the dying” from the alleyways of Calcutta, rather poor souls living on the streets, nursing them back to health for about 14 days, providing them with medical care, etc. That certainly is a relief in a country without social security. On the other hand, as early as 1994, the medical journal Lancet criticized the “homes for the dying," emphasizing that people in the hospice were deliberately left to suffer. A good 40 % of those collected die there, partly because the much touted medical care is limited to a minimum.

In diesem Zusammenhang interessant ist die BBC documentary Welcome to India, (engl., 3 Teile je 58 min) [still available 2025 on youtube] paints capitalist self-exploitation in rosy colors. One of the subjects makes a living by sweeping up the dust in the goldsmiths' quarter at night and diving through the mud and shit in the sewers, extracting 2-3 grams of gold per 80№ kg from the resulting mass of excrement. Note the residential area shown towards the end of the documentary, which he considers luxurious.

Before buying a ticket north, I tried travelling to Bangladesh. Theoretically, there’s a train connection, the Maitree Express, which operates twice a week. There’s an “International Booking Office” near the main post office (with a counter for philatelists and a small, worthwhile postal museum). The service I received was so poor that I had to use the “complaint book” the only time I went to India. It didn’t help, not so much because there were no seats available, but because the Bangladeshis make such a fuss about their visas that for a three-day trip to Dhaka, I would have needed two on the train and one at the immigration office ($ 20 in addition to the visa for the re-exit permit).

Two streets away, somewhat hidden away, is a local “booking office” der Eastern Railway (6, Sido Kanhu Dahar, Esplanade, Chowringhee North, Bow Barracks) with over twenty counters, specializing in domestic long-distance trains. Things went much faster there, but without a quota, which is hardly necessary anymore given the increasing use of computers. Calcutta-Howrah, the main station is on the other side of the river.

My next destination was Sikkim. First by train to Siliguri, a city of seven million inhabitants that hardly anyone in Germany ever has heard about. Its train station is in a suburb to the south alway referred to as NJP (short for New Jalpaiguri). The porters and touts were even more annoying than elsewhere. Around the station square, there are a number of food stalls, all of which call themselves “hotels” (like Australian pubs). They offer neither rooms nor toilets. Two mid-range hotels are located to the right of the square (about 300 meters down the road). Siliguri is known nationwide mainly for the fact that the Khalpara district is said to be the largest red light district on the subcontinent. Fresh meat regularly comes from the even poorer Nepal.

Sikkim

Permit und Anreise

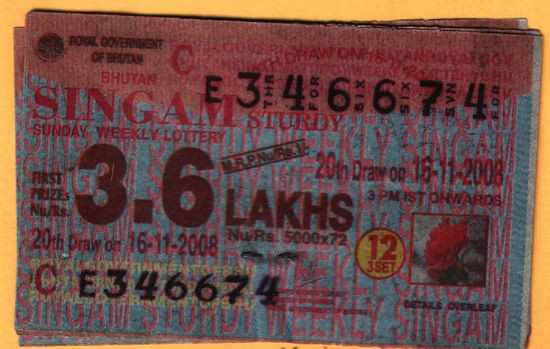

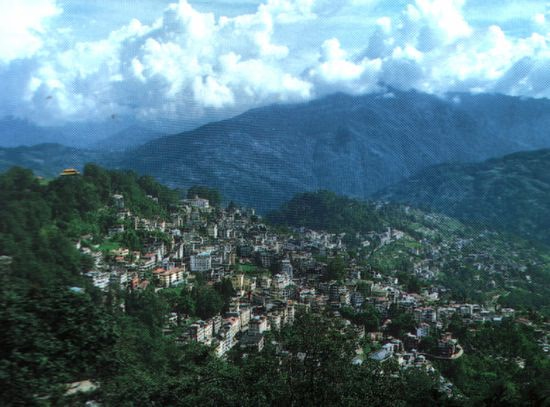

Sikkim was an independent principality until 1975 – albeit under British, later Indian “protection.” It is a strategically sensitive mountainous region inhabited by tribes of Sino-Mongolian ethnicity. The altitude made the temperatures bearable. The state is less closely tied to conservative Hindu tradition; alcohol is readily available, there is a lottery, a casino (since 2010) and arguably the only proper pedestrian zone in India in its capital. Overall, it is the cleanest region in India with extremely friendly people.

Foreigners need a “Protected Area Permit” which is obtainable at the Tourist Office in the twin cities of Siliguri / New Jaipalguri (NJP). The permit (with six carbon copies, two of which are for the traveller) is free of charge, if one brings an own pen – there’s no information provided at this “Tourist Office.” The Siliguri bus station is right next door. Halfway to Gangtok, one officially enter Sikkim for a maximum of 14 days. The passport stamp and permit are stamped at a checkpoint.

Gangtok

Overlooking Gangtok.

Gangtok is situated on a steep slope and the buses only go halfway up. With my sore foot, I trudged around a bend and into the first hotel I could find. The valley station of the local cable car was nearby. This tourist attraction is interesting in that they only sell return tickets (60 Rs). Indians don’t get off at the top, but all go straight back down. At the top of the mountain, however, is a beautiful Millennium Park and the Flower Show (10 Rs), famous for its orchid exhibition in spring. The lady at the counter talked me into buying some rather overpriced flower bulbs (there are also plenty in the city market). Another souvenir are cardamom pods (the black ones), which grow locally (200 g, 80 Rs). Despite my fears, there were no problems at customs in Frankfurt.

While waiting for my return bus, I lit a cigar I’d bought in Calcutta (25 for Rs. 360); a Corona-sized cigar — which caused quite a stir amongst the crowd of porters. I could have given the whole box away. In India, most people smoke are beedies,  , small, cigarette-like things made entirely of tobacco that smell pungent and quickly go out.

, small, cigarette-like things made entirely of tobacco that smell pungent and quickly go out.

Rumtek Monastery

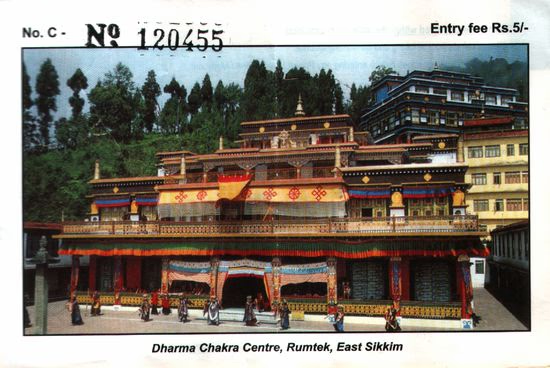

The next day, I visited the Tibetan monastery of Rumtek by shared taxi. It is 70 kilometers away by road (24 km as the crow flies). The head lama of the Karma Kagyu who lives there is significantly more politically active against China than the Dalai Lama. Indian soldiers guard the entrance, visitors sign a thick book and show their permit. 5 Rs entrance fee and it’s absolutely heavenly and quiet inside.

Darjeeling

Kanchenjunga (= Kangchendzönga).

From Gangtok back to NJP by bus, after a night in the better one of the two station hotels. As I checked in they sprayed my room with insecticide – half-dead cockroaches were still limping across the floor [“Baygon and they are bygone” if you excuse the pun, which certainly would be lost on the dying cockroach] Next day I took the toy train up to Darjeeling.

I had the good fortune that a steam locomotive pulling the train. I also manage to get a seat in first class. You don’t have to be a rail fan to enjoy this ride: 83 km in 8½ hours. That leaves plenty of time for picking of flowers from through the windows! Darjeeling town was established as a sanatorium by the English around 1840; it later became a summer capital. It maintains its colonial flair, even though decay is evident.

Darjeeling is at an altitude that it can get chilly at night in early November. Arriving shortly after dark, I managed to be the only guest at the first hotel I could find. Hot water was available by the bucket upon request. Service was nonexistent; the doorman, when he was there, was a keen collector of baksheesh.

The day I arrived and the next, there was a “bandh” (general strike). The Gurkhas, many of whom have immigrated in recent decades, are demanding an autonomous state of Gurkhaland. They have already designed their own car license plates. This is tolerated locally, but as soon as they drive into the lowlands, these cars are mercilessly confiscated by the central government.

Locomotive of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway. The line is 610 mm narrow-gauge; its highest point is 2,100 meters above sea level; the distance travelled 81.7 km. Scheduled travel time is 6½ hours. On a good day it takes 8 hours, occasionally 10. Steam locomotives are nowadays mostly used for special trips (since the 2010 monsoon season, the line was closed halfway up the route until 2015).

The region is, of course, world famous for its tea. It must be said that high-quality tea is practically unavailable in India. High-quality product is exported entirely via the tea exchange in Calcutta. A tea picker receives a basic wage of 30 Rs for her daily 18 kg of fresh leaves, 8 Rs for each additional kilo. Pay is a little higher for the smaller leaves from the first pickings. Several larger tea farms have set up shops in Darjeeling, where good quality tea is available. Unfortunately, the German customs for duty-free limit of 250 g was only lifted on December 1, 2008, so I couldn’t get hold of any for my return flight. [Germany imposes a (low) excise fee on coffee and tea, which until then was payable on private imports as well.]

Delhi and the flight home

I had already booked a sleeper car for the 1,800 km from NJP to Delhi. Halfway there, I joined the only other foreigner in the car, an American. We chatted with a very nice middle-class family who, very un-Indian, had only two children.

That train originating from Assam was already three hours late at NJP. By the time we arrived in Old Delhi station at 3 a.m. after 62 hours travel time, we arrived about 16 hours late. I would have stayed at the station until sunrise, but the lady insisted on getting a room immediately in the bazaar at New Delhi Station. So we rode through the night with an obviously suicidal tuk-tuk driver through Delhi to the Main Bazaar. I let her choose the room and negotiate the price. With my very sore foot, after six weeks of the heat and constant: “Hello Mister - where are you from? Want transport? Come to my shop?!” I was more than exhausted and very grateful for her help.

Among Sikhs – those gentlemen with the orange turbans – it’s customary for local temples (gurdwaras) to join forces once a year to hold a parade in which, alongside traditional costumed groups, free food is distributed. This procession, particularly large in the capital, lasted all of the next day. There were several “mobile kitchens.” What was striking, however, was that in particular middle-class Indians gorged themselves and threw away half-eaten plates in an almost disgusting manner. The truly poor ("untouchables"?) hardly dared approach – and I don’t even want to mention the millions of starving Negro children of India.

Somewhere in the Gangatic Plain. You board a train in the evening and see a landscape like this, with rice fields on either side. The next morning, 1,200 km away, you wake up and it looks exactly the same. Completely flat. It’s also clear why the hordes coming from the Kyber Pass, which descended on India every few centuries, couldn’t be stopped.

I still had two days left for shopping. Near the bazaar is New Delhi’s city center, Connaught Place. Three concentric ring roads form a prime location with shopping centers, bookstores, Wimpy’s, an English fast-food chain, which serves “mutton burgers" and has clean restrooms, etc. It has been deteriorating since I was there in 1994, but it’s still a “showpiece.” Beggars and cows are kept away – something I didn’t know back then. I was wearing newish black army lace-up boots. I’d just had them polished to a shine for 20 Rs ($ 0.70 at the time). The shoeshine boy had obviously been in the army and knew his trade: you could see your reflection. I was immensely pleased. Barely three minutes later, another shoeshine boy (he was walking with his utensil box over his shoulder) tapped me: “Mister, your shoes are dirty!” I shooed him away. When I finally looked down, I saw a lump of cow shit right smack on the front of my boot. Only later did I realize (no cows in Connaught Circle!) that an accomplice of shoe shine boy 2 had deliberately placed a load with a spoon. “Incredible India.” [This is the name of an international tourism campaign launched by the Government in 2002 to promote tourism.]

The tuk-tuk driver to the airport was a real rascal, like The Good Soldier Švejk, but very nice. [A metro has been running to the airport since January 2013].

I had 8.5 kilos of luggage on the outbound flight and checked 23 kilos on the return flight, on top of that my sweater, suit (theoretically subject to duty) and heavy boots I was wearing. I had also sent several packages of books ahead, weighing a total of 12 kg. I had lost 13 kg.

No whiskey was sold in the duty-free shops Europe destinations because the EU considers Indian security checks so unreliable that they cannot properly implement “bulletproof” packaging in plastic bags as has been implemented in the rest of the world. Two days later, the Bombay attacks occurred. All air traffic was temporarily suspended on November 26.

The five hours at the run-of-the-mill Helsinki airport passed eventually. The labelling domestic prices, so € 4.50 for a bottle of beer to go seemed cheap! After a night in Frankfurt, I was back in Munich by lunchtime. Open my door, chuck the backpack into a corner, run the bath – sheer bliss! Four months on crutches followed.

India = I’ll never do it again!

Addendum: The “free” flight

I had booked a flight on Finnair from Frankfurt to Delhi with a change in Helsinki for € 602.80 (return). Departure was Monday morning at around 6 a.m. Therefore, I arrived from Munich on Sunday by train with the „Schöners Wochenende“ [a type of discount ticket on weekends] and spent a few hours in the Mosel Eck pub, a charming dive in the Bahnhofsviertel district, with some characters. The aging queer “bartender” alone was quite a sight. As a “child of the seventies,” I grew up with only three TV channels and the big Saturday show—Thööööölke, Peter Frankenfeld, Hans-Joachim Kulenkampff and finally “Blauer Bock” The english equivalents would have been It’s a Knockout, Face the Music or Games Without Borders. So, I had to have a “Bembel” [the traditional jug  served in and made popular by the “Blauer Bock” game show]. My dear friends in Hesse: Äppelwoi [the sour type of cider served therein] is disgusting swill!

served in and made popular by the “Blauer Bock” game show]. My dear friends in Hesse: Äppelwoi [the sour type of cider served therein] is disgusting swill!

I took one of the last nightly S-Bahns to the airport and slumped down on one of the seats, which, even with a considerable amount of goodwill could hardly be described as “comfortable.” Finnair departs from Terminal 3, which is reached by a driverless monorail. As mentioned my ankle was already hurting quite a bit. At around 4:40 a.m., my flight wasn’t listed, no counter open yet. The ex-GDR employee at the information desk was friendly and competent [the stereotype of East German service being grumpy by default], something that couldn’t be said of the woman at the Finnair counter, which opened shortly after 5 a.m. After she spent a good 15 minutes trying to get my name into her computer – I was the only customer – it turned out that the flight to Helsinki had been cancelled (she couldn’t call any central office that early in the morning). After another 20 minutes, she managed to figure out that I had been rebooked on a direct Lufthansa flight to Delhi. That departed at 2 p.m., arriving three hours later than scheduled.

Back to Terminal 1 to check-in with Lufthansa. By about 10:00 a.m., I was bored to death; my foot was hurting terribly, the seats becoming unbearable. I would have forgiven Finnair had they presented me with a meal voucher and two hours in the lounge. The understanding Lufthansa lady said she wasn’t responsible, so I went back up three escalators and the monorail to Terminal 3 (damn foot!). The same lady was at the Finnair counter – I am polite describing her as “rude.” Final result: passengers travelling on wooden benches are not allowed in the lounge in Frankfurt and they can buy “international cuisine” at Burger King at their own expense.

Luckily, a few years earlier, those “overpaid bureaucrats at the EU in Brussels” had come up with a charta of “air passenger rights,” something the airport administration advertised on posters.

The procedure is as follows: 1) Submit a written complaint to the airline. 2) If it’s not resolved within 14 days, submit a written form to the supervisory authority (in Germany, the Federal Aviation Office in Braunschweig) and send a copy to the airline. With plenty of time to spare I headed to an internet cafe (@ outrageous € 3 for 20 minutes), search the Finnair website and submitted the “complaint form."

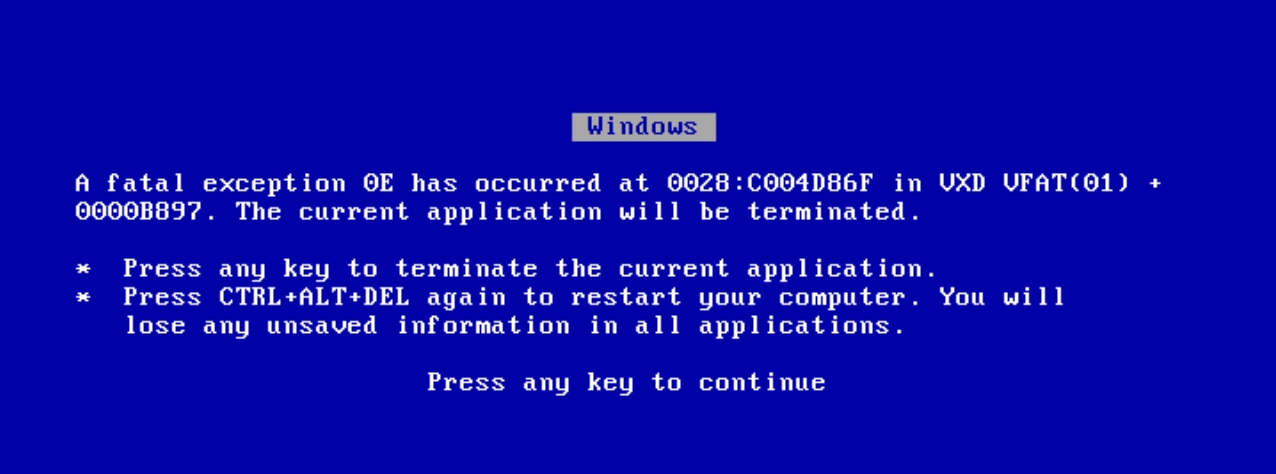

Getting ahead now: Three weeks later – I was in Kathmandu – I still had no reply. The email had vanished into oblivion. Now, it’s not exactly easy to find an internet café in K. with a printer capable of printing two six-page forms. The standard operating system across the entire subcontinent: Windows 98,  beacaus it didn’t have copy protection! (And a 56k modem is also a nice thing!) Next problem was how to file a written complaint with Finnair. I learned the importance of the German imprint requirement [Full postal address, eMail, person responsible]. In short, there was no mailing address, postal or electronic, anywhere on either Finnair’s German or English websites! Only overpriced hotline numbers and the aforementioned email form. After about 20 minutes, I discovered the address of the cargo department headquarters at Helsinki Airport.

beacaus it didn’t have copy protection! (And a 56k modem is also a nice thing!) Next problem was how to file a written complaint with Finnair. I learned the importance of the German imprint requirement [Full postal address, eMail, person responsible]. In short, there was no mailing address, postal or electronic, anywhere on either Finnair’s German or English websites! Only overpriced hotline numbers and the aforementioned email form. After about 20 minutes, I discovered the address of the cargo department headquarters at Helsinki Airport.

Next problem: buy airmail envelopes. As in all tropical countries, they are without adhesive, so I also had to find some glue. Then find the main post office – on the other side of town (my ankle extremely painful again). Since it was a holiday, only one special counter was open, but they kindly accepted registered mail. The day’s net result: Post two letters: 6 hours of messing about!

Two months after my return, I hadn’t heard from either the LBA or Finnair. So I sent out reminders. It turns out that the Finnair hotline is only open in the mornings, the Frankfurt representative office isn’t listed in the phone book and there doesn’t seem to be a mailing address either (only via Fraport, the airport operating company). Note: That was still unchanged in 2013. Service numbers now €2.96-3.12. In 2021, there’s at least an “imprint" at https://www.finnair.com/de-de by 2025 eben including addresses and German contact numbers.]

Weeks later, I received a letter from the LBA in Braunschweig stating that I apparently had legitimate cause for complaint, they would forward it to Finnair. In the meantime, I tried twice to get something out of the hotline (only € 1.80 per minute) – by this point, I was really keen on the € 600 I was due – (providing the problem number, “no, we didn’t get the email,” and all the other silly tricks …). I received a message from the post office stating that both registered letters from Kathmandu had been verifiably delivered. In the meantime, another run-of-the-mill letter arrived from Braunschweig.

Extremely now extremely annoyed, it so happened that Google found an internal PDF of Frankfurt Airport “for airline personnel only.” It had a Finnair landline number on it. The receptionist I reached was not just anyone, but actually the secretary of Finnairs chief of operations in Germany. She listened to my whining about the difficulties in reaching her boss (it was Friday noon) and requested that I write to her boss in English, as he couldn’t speak German. Alas that was no longer necessary. On the following Monday, a letter was in my mailbox stating that they would “generously” (and “without prejudice”) pay the € 600. No surprise that the bank transfer didn’t work out and required two more phone calls. All in all, the return flight cost me the grand total of € 2.80 for the Frankfurt-Delhi trip - plus postage, phone calls and a lot of nerves.