Your browser does not support .avif images. Please view on a modern desktop browser, released after autumn 2021. No apologies for not supporting Microsoft’s rubbish. View this page on the desktop mit Google Chrome from version 82, Opera from version 71, Safari from version 16.1, oder even better Firefox from version 93.

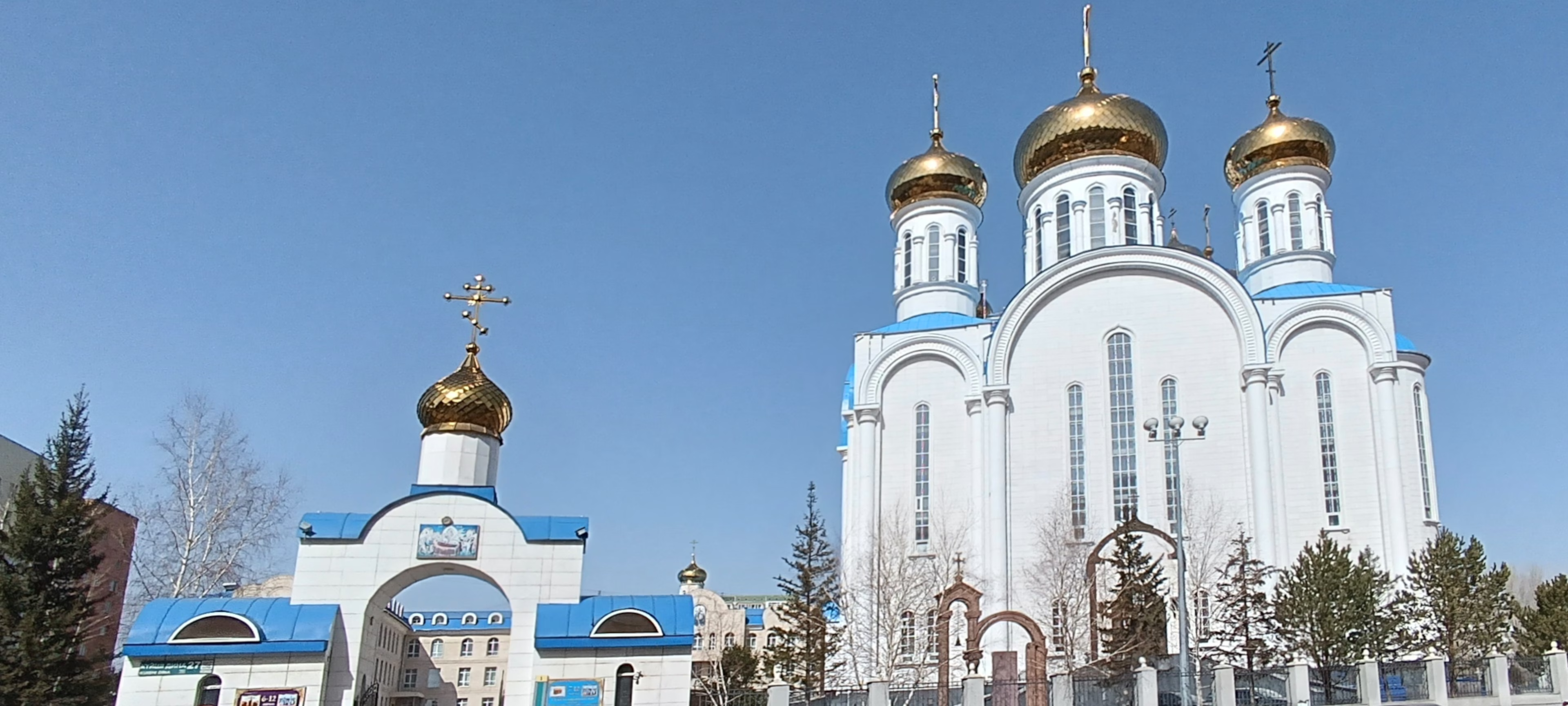

Bishkek, capital of Kyrgyzstan

Exchange rates: 1 € = 70–72 Som; 1 US$ = 58 Som; [June 2021 and May 2025: 1 € = 100 Som]

Normal income: approx. 20000, 35–40000 is considered very good [ø 2025: 39.000 p.m.].

Of the cities visited, Bishkek was certainly the most relaxed, which is probably also due to the fact that, unlike the other 'stans, the country has had two changes of president since 1991 (although there was outside “nudging” – Kurmanbek Bakiyev had to leave because he had dared to close the American air base).1 Like all cities developed during Soviet times, Bishkek is characterized by the almost complete absence of street signs (outside the city center), as well as house numbers or name. If you only want to ask for directions using sign language, as I had to do without Russian, you’re screwed, to say the least, especially at night!

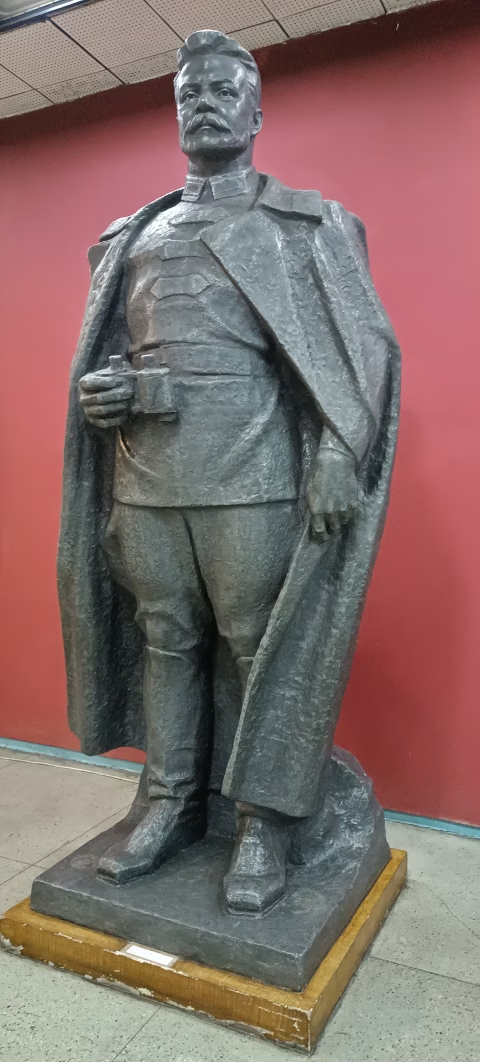

HE still shows the way. Alas, HIS statue has been moved from the main square to the rear of the National Museum.

Manas Airport is located about 33 km from the city. It can hardly be said to meet international standards. If necessary, you can get into the city by Marschrutka, (Not a taxi, but also not a real bus: the Russian minibuses with the pretty name “Marschrutka” are a type of public transport, which is particularly widespread in the regions. They can not be stopped by potholes, traffic jams or a lack of asphalt. The Marchrutka driver is a kind of superhero on the Russian streets: he can drive with one hand, make calls to the mother-in-law, collect the money from the passengers and give them change thereby bringing his right arm into unnatural positions. He can estimate the amount of the weight of the coins and at the same time answer questions about the route. All of this, of course, at maximum possible speed. Because: time is money.) that miracle of inefficiency that operates much of the former Soviet Union’s public transport system. These are converted station wagons (a la Sprinter) – mostly old German workmen’s vehicles, as the lettering makes clear – that can cram 10–15 people into them and basically never leave as long as there’s still room. With luggage, it gets tight. They serve certain routes irregularly at a fixed price. Otherwise, you’re at the mercy of the taxi mafia, who in Central Asia, even more than their counterparts elsewhere, are all crooks who cheat strangers. (I met only one decent, honest driver in my entire time.)

Shared taxis also cover longer distances between smaller towns, since there is no decent rail service and long-distance buses hardly run at all. They’re jam packed with at least five passengers, all of them carrying half their worldly possessions. It’s hard to imagine a more grueling ordeal than six hours spent crammed with three people into the back seat of an Opel Astra,  over bumpy roads, every single one a full backpack on their laps, especially as many men in the region emit a body odor similar to male goats due to their paperless toilet practices.

over bumpy roads, every single one a full backpack on their laps, especially as many men in the region emit a body odor similar to male goats due to their paperless toilet practices.

I arrived early in the morning on the first cold day of autumn. It was raining steadily, later followed by sleet at just below 6 °C, while I wandered around for 1½ hours under dim street lighting until I found accommodation that turned out to be lousy and overpriced. The Hostel Inn, centrally located at number 142 on the noisy Chuy Ave., the city’s central east-west axis. The bath consist of a 1.50 m square shower/toilet combo for 15–20 guests. This is ventilated into the four-person dorm, which can lead to considerable olfactory nuisance. Cleaning was superficial at best. Lesson learnt: Experienced travellers always bring a flashlight, earplugs and toilet paper.

Well, right at the start, I not only caught a bad cold, but also bought a down jacket for € 100 at the North Face store that would easily cost € 250 back home. Too bad it didn’t get cold again until the end of the trip. I was left lugging the thing around. Luckily, down compresses well. (I've since come to the conclusion that I got a Chinese fake, but it’s still warm.)

Bishkek city centre

_tn.avif)

_tn.avif)

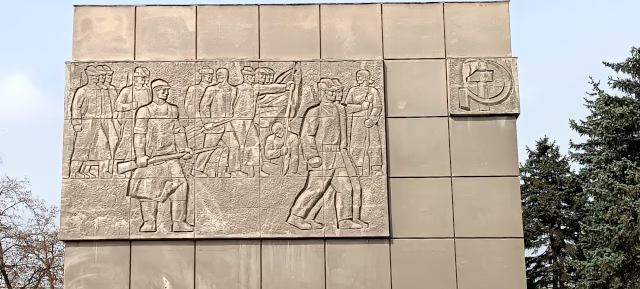

More images from the Kyrgyz capital, the traces of its Soviet past, art in public spaces and its less representative sides, can be found below in the section “One Week in Bishkek” 2024.

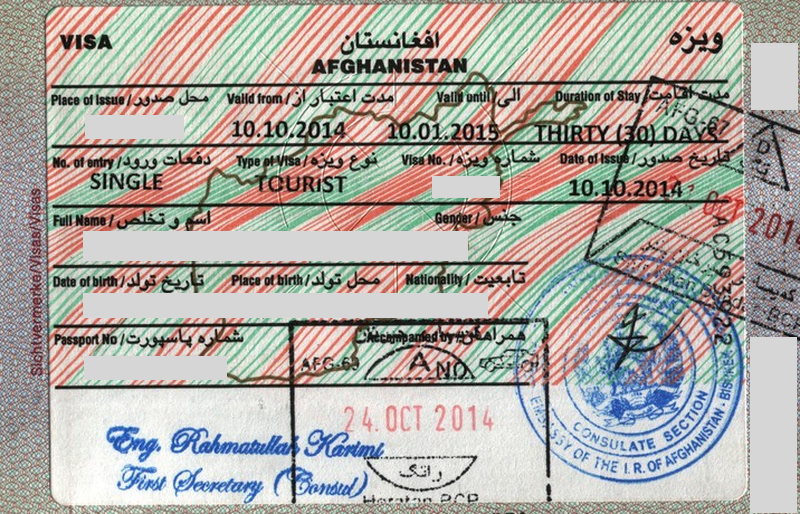

On the morning of my departure, near Osh Bazaar, I fell victim to some very convincing-looking fake police officers who robbed me of € 150 using the age-old “change your banknotes” trick. It wasn’t so much the amount that was annoying, but rather the fact that I was familiar with the scam and had been explicitly warned. At least I had the experience of spending the rest of the morning observing the not-so-efficient Kyrgyz police at work. A young, friendly Russian woman who I had met on the plane interpreted by telephone. The cops were clearly trying hard, probably because they were annoyed with the “competition,” but couldn’t spot the guys. It was understandable, really; they had earned enough for the next two weeks. Two policemen kindly drove me to the bus station and put me in the right minibus to Almaty. As the picture from a report by a Japanese tourist shows, at least I wasn’t the only one who fell for the scam. – And what can we learn from this? Genuine Kyrgyz police officers ALWAYS appear in uniform on their ID cards, even if they’re working in plain clothes. With the additional hole in my budget, after buying a down jacket and getting an Afghanistan visa, I decided to shorten the trip by ten days.

More » Bishkek 2024

Almaty and Kasachstan

Exchange rate: 1 € = 230 Tenge; 1 US$ = 180 T. [Juni 2021: 1 € = 508 ₸, May 2025 581 ₸]

Average income: ø 120000 ₸ (€ 530; 2024: 434.000 ₸ = 740 €), up-to-date rates of the National Bank.

View from the Avaritsya (Авразия-азс) rest stop on the Kazakh A2 highway between Almaty and Bishkek. 👆 Autumn 2014 and 👇 April 2024.

My stay was essentially limited to three days in the former capital, Almaty (formerly Alma-Ata). I only visited that because it was comparatively easy. Firstly, there are direct buses from Bishkek and secondly, the Kazakh government lifted the visa requirement for citizens of the ten most important investor nations for 15-day visits of any kind, effective July 15, 2013, “on a trial basis for one year.” This regulation was extended for another year in 2014. [In subsequent years, it was expanded to include all EU and EFTA citizens for 30 days.] Anyone staying in the country for longer than 30 days must have their lungs x-rayed and present a negative HIV test. This latter discrimination, in particular, is completely intolerable given that the town of Temirtau was the epicenter of the Central Asian AIDS epidemic. Large areas of the country are restricted areas and can only be visited with special permits, such as the Baikonur region (with the cosmodrome).

The registration requirement for foreigners (Of course, we also have registration forms in hotels and the obligation to register your place of residence with the municipality within 14 days, but what has to be done here within five calendar days is of a completely different calibre.) continues [even in 2021]. In principle, every foreigner must register by the fifth calendar day of arrival (including the day of entry). Better hotels will do this upon request. Non-CIS nationals can only register in Almaty and Astana. Theoretically, under the temporary suspension of the visa requirement, arrivals are automatically registered. This is recognizable by the two stamps affixed to the migration card. This only works reliably at the airport; it is often “forgotten” at land borders. Failure to register carries a fine of € 200.

The country is [was] an authoritarian presidential dictatorship where the finest personality cult is practiced around the “Kazakhbashi” Nursultan Nazarbayev. [Nursultan resigned in March 2019 but continued to act as a strongman in the background. The capital Astana – built from the desert during his term in office – was renamed Nursultan in his honor. Just three years later, it became Astana again.] For example, on the top floor of the Bajterek Tower, skyscraper/observation tower, for a fee, there is his handprint in gold  – it is said to bring good luck to ordinary mortals to place their hands there. In contrast to the other regional dictatorships, a comparatively large amount of money from oil and gas revenues is trickling down to the populace (with enough left over for the presidential clan), so that the standard of living of those still remaining in the country is higher than in neighbouring countries. Almost all of the “Volga Germans” resettled to Kazakhstan starting in 1941 now live in Germany. The Russians returned to their homeland, but still constitute the majority of the population in the northern cities. Prices, especially for food, are sometimes significantly higher than in Central Europe (for example, in the grocery section of Kaufhof). However, transportation costs (cheap gasoline) and accommodation are affordable.2 [The lifting of the price cap for LPG in January 2022 triggered the unrest in Kazakhstan in 2022, which, according to Western intelligence agencies, left approximately 225 dead and 4,300 injured, including 2,700 requiring hospitalization.]

– it is said to bring good luck to ordinary mortals to place their hands there. In contrast to the other regional dictatorships, a comparatively large amount of money from oil and gas revenues is trickling down to the populace (with enough left over for the presidential clan), so that the standard of living of those still remaining in the country is higher than in neighbouring countries. Almost all of the “Volga Germans” resettled to Kazakhstan starting in 1941 now live in Germany. The Russians returned to their homeland, but still constitute the majority of the population in the northern cities. Prices, especially for food, are sometimes significantly higher than in Central Europe (for example, in the grocery section of Kaufhof). However, transportation costs (cheap gasoline) and accommodation are affordable.2 [The lifting of the price cap for LPG in January 2022 triggered the unrest in Kazakhstan in 2022, which, according to Western intelligence agencies, left approximately 225 dead and 4,300 injured, including 2,700 requiring hospitalization.]

After the border, with efficient processing on both sides, the road initially passes through some mountains, where you can see sheep and goatherds on horseback. Soon it becomes flat … endless expanses. I won’t go into the many ecological disasters of this country, which, with rising global temperatures, will become a complete desert in a hundred years – already there is a region called the ”Hunger Steppe” (Betpak-Dala).

Almaty, formerly Alma-Ata

Almaty’s symbol – no worm in sight.

In the “City of Apples,” people are proud that the ancestors of the Prunus genus originate from the region. Anyone who knows me understands why I dislike the place for that reason alone. Almaty is a massive city that grew rapidly during Soviet times in a checkerboard pattern. It has no actual city center. Orientation is difficult without Russian; the only useful signs with street names above the respective cross streets serve the numerous drivers. As everywhere in the region, street signs on buildings are scarce, house numbers are rare and doorplates with numbers or names (This custom dates back to the good old Soviet times – the men in the long black leather coats from the KGB didn’t know who lived where when they came to pick someone up in the dead of night.) are completely unknown.

It is pleasantly noticeable that people adhere to traffic rules. Even at 2:30 in the morning, people slow down at zebra crossings for pedestrians. Some drivers even fasten their seatbelts.

Thanks to my gullibility, I had spent the morning at the police station in Bishkek and, after a five-hour minibus ride, only arrived at the out-of-town bus station just after dark. With me on the bus was an English woman writing her master’s thesis on Kazakh environmental problems and a, let’s say, “somewhat odd” German man who at least knew his way around the bureaucracy. In Kazakhstan, “any car is a taxi,” only the price is negotiable. Somehow, I made it near my accommodation, then spent 20 minutes in a dark backyard trying to find the place. They promptly booked it out. They very helpfully organized a room for me at Hostel 74/6 via Google Maps and phone, which turned out to be a hit at around € 10. Newly renovated, clean and with functioning plumbing, I even had a cute cat as a roommate. The next day, I was joined in my room by a Russian man with the same BMI as me, who, without being asked, but who was obviously knowledgeable, informed me about the prices of “women for one night” in various cities. Later, a Japanese guy who spoke unusually good English and had an exceptionally good sense of humor joined me.

Since a nationwide gambling ban (except for sports betting and lottery tickets) has been implemented, the town of Kapchagai (Qonajew) is being developed into one of the “gambler’s reserves” and the “Las Vegas of Central Asia.” Today, there are almost fifteen casinos there. I haven’t gone there [even in 2024].

Towards Tashkent

I then took the night bus to Shymkent. The planned departure time was 6 p.m., which was when we drove to the gas station, then back again to spend a solid two hours loading up flat-screen TVs in every available corner. The fare is tiered. The further back you sit, the cheaper it becomes. The last rows cost a third less than the front.

Theoretically, minibuses travel the 120 km from Shymkent in Kazakhstan to the border crossing, but I only found one taxi at a special foreigner’s price. The remaining twelve kilometers into the city can be covered by taxi (2014 per vehicle, up to 4 people, 20,000-40,000 som depending on your negotiating skills). The journey with Marshrutka 82 from northern Tashkent (Buyuk Ipa Yoli metro station, formerly “Maxim Gorki”) to the center from the border village is considerably less comfortable with luggage. A shuttle bus is available for the remaining distance.

Usbekistan

Black market exchange rate: 1 € = 4000 Som [June 2021: 1 € = 12600 Som]; 1 US$ = 3120 Som

official subsistence level (2011): 202000 S., average income 600000 before tax, 400000 net.

Welcome to a rather nasty police state

Uzbek visa. For multiple entries and exits, the stamps are stamped on a different page. Only on the last exit is one stamped on the visa. [Since the beginning of 2019, Europeans have been allowed to enter the country visa-free for 30 days.]

You are ruled over by Islam Karimov the First (President of Uzbakistan), as can be read on numerous newly built monuments.3 He likes to see himself, perhaps not entirely free of Caesar-mania, as the successor of Tamerlane (1336-1405. In European historiography better known as Timur. From 1370 to 1507, the Timurid Empire flourished in the area of today’s Afghanistan, Iran and Uzbekistan. The capital of the Timurids was initially Samarkand, later moved to what is Herat in Afghanistan today. A branch of the dynasty conquered the Delhi sultanate in 1526, transformed it to the realm of the Great Mughals until its fall to the British in 1857.) (called “Amir Timur” in Uzbekistan). Remember, he was in spirit descendant of Genghis Khan, who, in the 15th century, devastated the region with his scorching and murdering horde, leaving little. Falsifying history, Timur is being built up as an national symbol, the “forefather of the Uzbeks.” Historically, this is nonsense; the ancestors of the Uzbeks only emerged from somewhere out of the steppe onto the stage of world history two hundred years later – equally keen on raping and pillaging.

Karimov, a relic of the Soviet Politburo, has ruled with an iron fist since 1990.4 Especially since the Andijan massacre, (In Wikipedia On 13 May 2005, protests erupted in Andijan, Uzbekistan. At one point, troops from the Uzbek National Security Service (SNB) fired into a crowd of protesters. […] It was claimed that calls from Western governments for an international investigation prompted a major shift in Uzbek foreign policy favouring closer relations with autocratic nations, although the Uzbek government is known to have close ties with the U.S. government and the Bush administration had declared Uzbekistan to be vital to US security because it hired out a large military base to US military forces. The Uzbek government ordered the closing of the United States Karshi-Khanabad Air Base …

) which left at least 400 dead (officially 9), “Islamists” have been treated not with soft gloves. While that’s not a bad idea in itself – after all, Muslims aren’t tolerant of others – boiling prisoners to death is a bit excessive. The Americans also tortured here (So-called “enhanced interrogation” cf. Folter und die Verwertung von Informationen bei der Terrorismusbekämpfung. Die Fälle Kurnaz, Zammar und El Masri vor dem BND-Untersuchungsausschuss. This is not the place to deal more precisely on the complicity of the current German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier who as Foreign Minister was deeply involved in covering up the detention and torture of German citizens by US forces worldwide.) until they were expelled from the airbase. British Ambassador Craig Murray found this unbearable; he took the excesses to the world press and was promptly dismissed from the diplomatic service as being detrimental to UK policy.5

But now enough raging, my experiences:

Tashkent

The border crossing near the capital, Tashkent, on the Uzbek side lived up to the horror stories travellers tell. Although, like many of Uzbekistan’s land borders, it is closed to vehicular traffic (due to Uzbekistan’s deliberately poor relations with almost all of its neighboring countries), numerous migrant workers benefit, particularly during the cotton harvest, from the significantly better wages and shopping opportunities in the neighboring country.

The Kazakh side is still comparatively efficiently organized. Customs showed little interest in outgoing travellers. It was busy enough to require a queue of about 20 minutes at the passport control counter. Europeans with many stamps in their passports are still a rarity, so they take time for a brief interrogation – I don’t speak Russian anyway (“pa russki nyet!”) and English certainly not in situations like this. The policeman flicking through my passport was confused by my visa for Nagorno-Karabach  and asked his colleague:

and asked his colleague: Where is that?

Armenia.

On the Uzbek side, the tone becomes considerably rougher. Processing doesn’t happen at the speed of an Aldi checkout, more like a post office counter. Next to me in a jostling crowd was a Russian who, at 10:00 in the morning, was so intoxicated that just catching a whiff of his breath made you drunk. He proved to be quite civil, though, even if he did occasionally hold on to someone’s shoulder. An hour later, about 20 people had been processed at the two open counters. We went into the customs building, where the pushing and shoving continued until customs declarations had been filled out in duplicate amidst mountains of bags and suitcases. We were let into the actual inspection area one by one through a barrier guarded by a soldier, who was already checking to see if everybody had filled out the forms. Now “Ivan the Drunk” was right in front of me. He mumbled and held a crumpled piece of paper out to the soldier. I don’t understand Russian or Uzbek, but the reply was clear: “You drunken pig, shove that slip somewhere else. Make sure you bring back a new one, filled out properly and get lost now, right now! Dawai! Dawai!” The customs officer checking my slip then asked in English if I was coming to work. When I replied, “No jobs here,” he had to grin. After scanning my luggage, I was relatively quick out the back door.

The money changers at the café at the exit have, of course, “never” heard of a bus to Tashkent. In fact, you have to take a marshrutka to the bus station, from there you take line 82 to the north of Tashkent (metro “Buyuk Ipa Yoli,” formerly “Maxim Gorki”). With a bit of skill, you can haggle taxis down from 40,000 to 20,000 som. On the outskirts of the city, my experience of the police state for the second time – everybody gets stopped at a checkpoint, complete with watchtower and a pillbox by the side of the road. These things can be found throughout the country at every major highway intersection, town exit, or provincial border.

Legally, foreigners cannot purchase a SIM card in Uzbekistan [apparently permitted since 2017]; 10-day tourist cards are only available at the telephone company headquarters. However, one might find someone in a bazaar who will buy a card in your name for a commission. In such countries, even a law-abiding European has to get used to the fact that a lot of behind-the-scenes dealings take place and that this is relatively safe because the surveillance system, which in Germany has been systematically expanded down to the smallest detail since 1976, is simply not that advanced yet. Internet café operators are only allowed to provide devices that do not have download capabilities (USB ports). This was particularly annoying, as I had scanned my personal travel guide on the flash drive to save weight. I've been told that sites like YouTube or Facebook, or anything in the slightest “Islamist” or critical of the government, are more often down than up. (This also applies to Tajikistan and, to a somewhat lesser extent, Kazakhstan.)

The city of Tashkent, largely destroyed by an earthquake in 1966, is spread out, but thanks to the metro, which is still under construction (1,000 Som per ride = € 0.25), it has a decent public transport system, supplemented by six tram lines. [All tram service was ended in May 2016.] Photography is prohibited in and around all public transport facilities throughout Uzbekistan. On the last day, I actually had to delete a picture of a mural in the subway from my phone.

Security becomes really annoying when you take the subway. At every staircase to the mezzanine level there is a guard who (in theory) has to inspect the carrier bags of everyone going in. At the escalator to the platform there is another guard with a scanner to x-ray bags and people if necessary and to check papers. When on the second day by 1 p.m. I was stopped for the third time this time by someone who was obviously of higher rank (judging by his badge), said “Passport!” again, I lost my temper: I told him in perfect Bavarian what I thought of him and his checks. Completely stunned, he took a step back. He immediately recovered, cursing back in Russian. I gave him a copy of my passport, which he then just looked at briefly and off I went. When I told this little anecdote to my Russian friends that evening, their reaction was sheer disbelieve. A local talking like that to a law enforcement officer can expect at least an unpleasant afternoon at the police station. Strangely, after that I was never stopped, even though I used the subway frequently every day.

Spooked by warnings about the mandatory registration of foreigners (The German Foreign Office warned: Innerhalb von drei Tagen müssen sich Ausländer (ausgenommen Diplomaten) beim UVViOG (Verwaltung für Ein-/Ausreise und Staatsbürgerschaft, ehemals OViR) des jeweiligen Stadtbezirks anmelden. Bei einem Hotelaufenthalt übernimmt das Hotel die Registrierung. Bitte beachten Sie, dass bei Einreise mit einem Touristenvisum eine Registrierung nur über Hotels erfolgen kann. Sofern Sie anderweitig, z. B. bei Familienangehörigen oder Bekannten unterkommen möchten, muss Ihr Gastgeber vor der Visabeantragung seine Einladung beim UVViOG zur Beglaubigung vorlegen. Der Einlader muss anschließend die Einladung bei der Konsularabteilung des usbekischen Außenministeriums vorlegen. … Im August 2012 wurden die Bestimmungen über Einreise und Aufenthalt dahingehend verschärft, dass ein Ausländer bei Verletzung der Aufenthaltsbestimmungen abgeschoben werden kann mit der Folge einer Einreiseverweigerung von einem bis drei Jahre. Als Verletzung des Aufenthaltsrechts gelten hierbei ein Aufenthalt ohne bzw. mit ungültig gewordener Aufenthaltserlaubnis sowie die Nichteinhaltung der Bestimmungen über die Registrierung bei vorübergehenden oder längerfristigen Aufenthalten. Einzelreisende, die sich ohne hinreichende Orts- und Sprachkenntnisse (russisch/ usbekisch) nach Usbekistan begeben und mit einem Touristenvisum einreisen oder ihren Aufenthalt vor Ort verlängern möchten, müssen aufgrund der strikten Vorschriften für die Einreise und den Aufenthalt des öfteren mit Schwierigkeiten rechnen, … Bereits minimale Überschreitungen gültiger Visa ohne rechtzeitige Verlängerung … führen bereits zur Ausweisung mit erheblichen Einschränkungen der Bewegungsfreiheit unter Einbehaltung des Reisepasses. Im Regelfall wird eine hohe Verwaltungsstrafe verhängt, und es muss mit einem Verbot der erneuten Einreise gerechnet werden. … Der Registrierungsbeleg ist Voraussetzung für die Buchung von Flügen bzw. Fahrkarten für Reisen im Landesinneren und muss bei der Ausreise vorgelegt werden. Die Einhaltung der melderechtlichen Vorschriften wird von den zuständigen usbekischen Behörden erfahrungsgemäß genauestens überprüft. Die Mindeststrafe bei Missachtung der Vorschriften beträgt ca. 700,- €.

von: http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/DE/Laenderinformationen/00-SiHi/UsbekistanSicherheit.html 2014-11-19. This has barely changed by 2024.) — officially, any private overnight stay is prohibited — I stayed at the Mirzo B&B – yet another misguided recommendation from a certain English language travel guide. Overpriced by local standards, with rarely warm showers. With an attached travel agency, the somewhat shady operator happily profits from poor exchange rates and excessive fees. The next day, I moved into the much better-run, cheaper Gulnaras Guesthouse where breakfast was included. A lovely courtyard furnished with sofas and tables made the stay bearable.

I then spent the weekend as a couchsurfer with a Russian, where I gained deeper insights into living conditions in Uzbekistan.

Tashkent Vokzal the main train station, previously known as Severnay Vokzal (“Northern Station”) until the southern Yuzhni Vokzal was closed. It is appropriately located south of the New Town at the end of Tashkent Street. Access to the extensively cordoned-off station building is only possible after a thorough security check, ticket check and passport check. The rules are less strict at the bus station, where you only have to go through a scanner. “For security reasons,” there is a nighttime bus ban in the country. Given the vast distances, this means that buses only depart early in the morning. The journey from Tashkent to Samarkand takes approximately 4–5 hours, covering a distance of 290 km. “Rest stops with sanitary facilities are unknown” was how the German Foreign Office phrased it.

Samarkand

Samarkand is Uzbekistan’s national showpiece; its historical sites have been extensively restored with foreign aid. When UNESCO added the inauthentic restored madrasas and mausoleums to its World Heritage List, it clearly succumbed to pressure from the dictator and softened its strict standards regarding historicity. Virtually all of the old buildings date from the period following the Mongol invasions, even though Samarkand has a much longer history. Even those constructed in the 15th to 17th centuries had fallen into complete disrepair under the cruel, slave-owning sultans (Given this history one could argue that the Karimov dictatorship is not atypical. Cf.: Encyclopaedia Iranica: CENTRAL ASIA In the 18th-19th Centuries) before the Russian conquest in the second half of the 19th century. Islamic rulers have no appreciation of history or art. It was only during the Soviet era, partly as a result of increased immigration to the Central Asian republics from 1941 onwards, that the cityscape was significantly improved.

Timurid Mausoleum (Go'r Amir Maqbarasi) and Registan

(Note about the photos: Not all leaning towers are due to poor cell phone camera quality or parallax error. Several of the buildings shown are actually not plumb.)

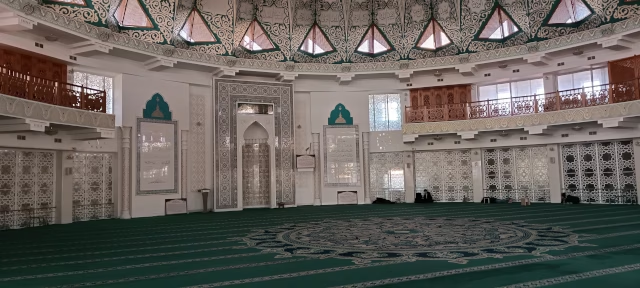

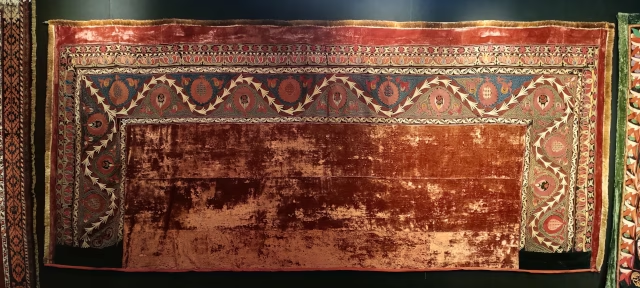

There are many more mosques to visit in Samarkand, such as the Juma or Bibi-Khanym Mosque. Also the old city center with the Ulugʻbek Observatory. In terms of style, they hardly differ from the ones pictured here. Therefore, no photos. At least my obsession with blue tiles (more), which I've had since a school trip to the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, was catered for.

My accommodation, “Bahodir B&B,” 132 Mullokandova St. (facing the Registan’s main entrance, about 50 meters to the right to the wide footpath, 150 meters through the park, at the first fork (in front of the ice cream parlor) turn right, about 30 meters on the left side of the street), turned out to be a great find. The prices for a dorm room of US$ 10 or a single bed in a triple room for US$ 15 are reasonable, although I treated myself to the luxury of a single room, if only because the shared shower wasn’t that great. A friendly family business with a cozy courtyard, including a hearty breakfast. Very popular with the French and Japanese.

In the Bahodir-Hostel truly great rulers are admired. [Pictured on the flag is king Ludwig II. of Bavaria, murdered 1886 after a reactionary coup. A homosexual visionary and admirer of Wagner’s operas who gave the world Neuschwanstein Castle (not the one in “Disneyland”) – he is to this day frequently referred to as “Fairy tale king”.] (A Karimov statue is in the park around the corner.)

Due to time constraints, I decided not to make my originally planned tour to northern Uzbekistan, via Urgench (approx. 700 km) to Khiva , which is 35 km away and worth seeing because of its preserved, lively old town. I also cancelled the onward journey to Nukus, located north of there, which would have been interesting because of its Igor Savitsky Museum of banned Soviet Art. From there, you could have taken a day trip to Moynaq, 220 km away, to the former shore of the Aral Sea, including its “ship graveyard.” It should be remembered that the ecological catastrophe of devastation is (in the truest sense of the word [The German „Verwüstung“ means “desertification” as well as “total destruction”]) entirely man-made. The lake could be refilled to its previous level within 6-7 years if only Kazakhstan and even more so Uzbekistan would abandon cotton cultivation and the associated irrigation. In Uzbekistan in particular, cotton cultivation is still firmly in state hands, with harvest proceeds accounting for about a third of state revenue. The harvest is mostly carried out by hand by people otherwise employed by the state, as a form of corvée. (Cf.: Forced labour in Uzbekistan: In the land of cotton; The Economist. 2013-10-16) State employees and many schoolchildren aged ten and over, are “sent to the countryside” and paid so poorly based on the amount they harvest that they have to bring money with them for their stay (Uzbeks only tell foreigners such things in their private homes after a few …). [In 2014, the practice of sending schoolchildren to the fields for up to two months ended. Since the privatization of cotton cultivation in 2019, forced labor has nominally been abolished. Private sector restrictive contracts with high quotas are still being imposed on farmers by state buyers in 2020.] I also didn’t go to Shakhrizabz, which would have been on the way to Termez, after several visitors who had been there advised against it due to extensive construction work in the area of tourist interest. Instead, I finally got to travel by train, in a 3rd-class couchette (Russian: “platzkart”). Classic Soviet broad-gauge carriages with four beds in an open compartment. When purchasing a ticket, you must present your passport, which is compared with the number on the ticket upon boarding. The provodnik was of the usual sour type, but reasonably efficient.

Termiz

For once, the Hotel Surxon (aka “Surkhan”), renovated in 2018, proved to be a rip-off-free place to stay and at 35,000 som (€ 9 2025: from € 20/double), it’s definitely worth the money. Aside from the usual plumbing issues common to Central Asia, it’s a really decent, well-equipped hotel, including air conditioning, massages, a fitness room, a buffet and a hair salon. While it was probably the best value in town in 2014, it looked considerably more expensive from the outside. It’s often used by local couples during the day for extramarital sex, which can be clearly heard through the thin doors.

The situation is quite different at the Archaeological Museum, founded in 2002 by order of Karimov, the First (President of Uzbekistan). The price for foreigners is exorbitant: 20,000 Som, while locals pay only 500 S. Six kilometers from the modern city center, whose main axis is Al-Termizi St., there are some excavated ruins of the ancient Buddhist monastery of Fayaz Tepe dating back to the first centuries CE. Due to its close proximity to the border fence, a large part of it lies within a restricted area and the excavations themselves are still ongoing. Those with a museum ticket can also visit there. Photography permission costs extra.

The pleasantly shady, large city park offers, in addition to the usual Soviet-era attractions—rusty carousels, etc. — a large artificial lake for swimming with a water slide, drained in winter and certainly welcome in summer. The place is considered the hottest in Uzbekistan, with maximum temperatures recorded from June to August reaching 50 °C and the average daily high of 38–39.7 °C

Even after the withdrawal of German combat troops from Afghanistan, which occurred around the time of my visit, Termez Airport remained in use by the Bundeswehr, which had had a base there since 2002. A new, secret lease agreement (The German Bundeswehr sent up to 5350 soldiers to fight with ISAF. Details of the 2005 agreement: Dr. Pflüger »rettete« Termez, 2005-12-27. Its extension 2015: Neuer Geheimvertrag mit Usbekistan, 2015-01-05. „Bis Dezember 2015 fungierte Termez als „Safe Haven“, um im Notfall alle deutschen Soldaten schnell aus dem Einsatzgebiet in Afghanistan evakuieren zu können. Am 20. Dezember 2015 wurde der Strategische Lufttransportstützpunkt vom letzten Kommandeur, Oberstleutnant Thomas Blätte, geschlossen.“ https://de.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Strategischer_Lufttransportst%C3%BCtzpunkt_Termez&oldid=192699800) was negotiated in 2015 to serve the then-remaining 850 non-combatant Bundeswehr soldiers.

Hairatan border crossing

View of the Afghan “port” of Hairatan ( حیرتان ) from the Friendship Bridge.

The only way to get to the border post is by exorbitant taxi; the local marshrutki are all Isuzu minibuses with absolutely no room for luggage. I've described the border crossing procedure on wikivoyage.8I must note, however, that I had few problems leaving the country, even though Uzbek customs officers are notorious here. This was certainly due to the fact that, for the first time, the picture of Hitler  inserted in the back of my passport helped me. (Aside: I personally have nothing to do with Adi, as is well known, but I heed advice given by the Därrs. (The Därrs were a couple pioneering Sahara crossings in VW. They also travelled through Asia in the 1970s, wrote books about it and ran a long-famous outfitter’s shop in Theresienstraße in Munich. One of their tips was putting a picture of Hitler behind the windshield when travelling to Muslim countries.) After the customs officer discovered the picture, the enthusiasm for a strong Germany that can be heard everywhere in the region followed: Most people know about FC Bayern, Mercedes, Hitler and, unfortunately, increasingly also “Mrs. Merkel,” who enjoys a reputation for her economic policies – “there is no alternative” somewhat upsets me.

inserted in the back of my passport helped me. (Aside: I personally have nothing to do with Adi, as is well known, but I heed advice given by the Därrs. (The Därrs were a couple pioneering Sahara crossings in VW. They also travelled through Asia in the 1970s, wrote books about it and ran a long-famous outfitter’s shop in Theresienstraße in Munich. One of their tips was putting a picture of Hitler behind the windshield when travelling to Muslim countries.) After the customs officer discovered the picture, the enthusiasm for a strong Germany that can be heard everywhere in the region followed: Most people know about FC Bayern, Mercedes, Hitler and, unfortunately, increasingly also “Mrs. Merkel,” who enjoys a reputation for her economic policies – “there is no alternative” somewhat upsets me.

The “Friendship Bridge” between Uzbekistan and Afghanistan.

The "Friendship Bridge" (Мост Дружбы), built in 1982, between Uzbekistan and Afghanistan, can be crossed on foot . The beginnings of a railway line were built during Soviet times. The Americans then expanded it into their camp in Mazar. There is no passenger traffic, except for people trained to kill professionally.

The customs officer was not interested in the registration certificates I had diligently collected. The customary body search, which one hears can extend to every bodily orifice, was a cursory pat-down of my jacket. I only had to empty the bottle of vodka after taking a hearty swig, because: “Islamic Republic in Afghanistan.” The customs form was also stamped blindly. The exit stamp in my passport came after a short wait, followed by the walk across the “Friendship Bridge,” which is well-secured on the Uzbek side. It was built by the Soviet Union in 1979, demonstrating its unbreakable friendship with the Afghans. The Americans – thrown out (Up to 7,000 troops were stationed at the Khanabad military airport, or K2 for short, in “Camp Stronghold Freedom” since 2001. In 2020/21, around 70 American veterans who now had cancer claimed that the cause was the radioactive and oily filth left behind on the Soviet-era base. A congressional hearing was held on the matter. The Department of Defense denied any connection. (https://phc.amedd.army.mil/PHC%20Resource%20Library/EnvironmentalConditionsatK-2AirBaseUzbekistan_FS_64-038-0617.pdf). It’s always interesting to observe the whining reactions of people whose job it is to kill women and children. The CIA broadcaster RFE/RL reported in April 2021 that the Biden administration is again seeking bases in Kyrgyzstan (Manas Airport was used from 2002 to 2014) and Uzbekistan. (https://www.rferl.org/a/u-s-military-bases-in-central-asia-part-two-/31219781.html) by the Uzbekbashi in 2005 after daring to criticize a massacre of 400 civilians6 – and the German Air Force, which was stationed at Termez Airport, used it to build a railway line to supply the occupation troops.

A lovely piece of the Hindukusch to defend. [Peter Struck, the Minister of Defence justified German troops posted to Afghanistan by saying: “Germany is being defended in the Hindukush.”]

“Germany is being defended at the Hindukush”

Exchange rate: 1 € = 68–70 Afghani [June 2021: 1 € = 93 Af.]; 1 US$ (= 50 Afghani) circulating as a second currency.

Monthly income: agricultural labourer 2000 Afg.; US$ 45 (postman (“Habibullah Hakimi has been a postman in Kabul for 36 years.” … After deducting € 12.50 for state pension insurance, Hakimi is left with a net monthly salary of € 45. He has no health insurance and he doesn’t have to pay taxes on his low income. He and his family live rent-free in his son-in-law’s house. There is no electricity there; they get their water from a well. Hakimi spends almost two-thirds of his income on basic foodstuffs. Because his wife was ill, he owes € 1,200 to relatives.” Postbote in Afghanistan by: https://web.archive.org/web/20150702211710/http://www.brandeins.de/archiv/2008/mythos-leistung/ein-postbote-in-afghanistan/)); Manager 12000 Afg.; President Karzai: US$ 500 (officially). Unemployment 35–40%.

“Destroyed the forces of the Crown,

With thirty thousand they began,

Just one returned from Afghanistan”

Fontane, Das Trauerspiel von Afghanistan.

I won’t digress into politics again, but after a week in the former German zone of occupation in northern Afghanistan, I have the impression that this entire operation and the propaganda surrounding it were made to appear palatable to the dumb German people as “humanitarian.”[Anne Will’s TV show] was the biggest hoax since 1939! As of summer 2021, I have to change the wording here. It should read: "Between the Polish army’s attack on the Gliwice radio station and the CDU/CSU [conservative] government’s measures to supposedly protect against coronavirus. Many things come to mind, but they should be properly documented and linked, some of them in note 7 below.

Regarding Islam, I agree with the comedian Volker Pispers: “Religion is for people who can’t handle alcohol.” The Austrian comedian Gunkl also goes on concludes, for almost 20 minutes, „über Wüsten-Religionen, Wissen, Respekt und Kränkungen“ [“about desert religions, knowledge, respect and insults.”]

Easily available in Bishkek for US$ 81 the same day or the next day.

… the most turbulent race under the stars. To the Afghan neither life, property, law, nor kingship are sacred when his own lusts prompt him to rebel. He is a thief by instinct, a murderer by heredity and training and frankly and bestially immoral by all three.

Rudyard Kipling, The Amir’s Homily

During my week-long stay in Afghanistan, I didn’t meet a single white person on the street. Only one man, obviously of Indian descent, sitting on a park bench near the Ali shrine, betrayed his foreign origins through his clothing. We didn’t talk.

In Mazar, the population is comparatively open; many try to use their few words of English and people unobtrusively look at you and smile at you. The situation is different in Kunduz – apart from extremely persistent female beggars – you are only stared at silently, with the attention conspicuously often focused on your shoes. I suspect army boots would have been the wrong footwear here. However, if you approach the people (mostly traders), you will be treated helpfully and decently, although there are a few exceptions that prove the rule.

Masar-e-Sharif

Immediately after crossing the border, the tea stall owner exchanged my dollars for Afghanis at a poor rate. A waiting taxi driver was then persuaded to drive me the nearly 70 kilometers to Mazar for US$ 20, making it clear that I had no objections to additional passengers boarding along the way. The road largely runs parallel to the railway line, but is threatened by sand dunes. A striking feature were the small, uniformly styled houses built at short intervals, slightly off the road, clearly housing security forces.

From the Uzbek border, we drove 75 km down the road to Mazar-e-Sharif (Mazāri Sharīf, Farsi: مزارِ شریف) through nothing but desert, with shifting dunes sometimes threatening the road. The desertification of the area is exacerbated by the population explosion, including the goats, which devour all the dry bushes that still grow. To the left of the main road is the new single-track railway line built to supply the occupying troops between the border, from where there is a connection to the general Central Asian railway network and to Camp Marmal. No thought was given to passenger transport for the local population. Instead, there are several police stations, built according to a standardised blueprint, only to fall into disrepair after just a few years, “inhabited” by members of a people to whom the concepts of maintenance and cleanliness in the Western sense are completely alien and probably impossible to convey. (Now, the Oriental in itself is – beginning with the Semitic tradition that fraud is only punishable if committed against a fellow believer – dishonest in our understanding. Even the concept of “human rights” is completely alien to Muslims: “Many women pour gasoline over themselves and then set it on fire. Women and young girls who see this as their only remaining means of escape, an unwanted marriage or punishment from their male family members for ’shameless behavior,’ such as going out on the street without a male escort. In Herat alone, in the second half of 2004, over 150 girls and women chose this gruesome act of self-mutilation over possible punishment. Equally horrific are the injuries women inflict on themselves for the reasons mentioned, such as swallowing panes of glass or razor blades, needles, or the like.” Source, with further detailed descriptions of audacity. There’s no way of helping these ignorant bigots, but one can’t allow oneself to be exploited at will. [Wir schaffen das

was proven, as of 2025, a total failure]. Therefore, put a lid on it and flush them down the drain (may allah be merciful on them), as long as “tolerance” doesn’t lead to mutual give and take.) In return, with an illiteracy rate of 49 % for men and 82 % for women, one suffers from the highest infant mortality rate of 191 per thousand.

The center of the city is the Ali Mausoleum ( روضه شریف ), the "Blue Mosque" (Rawza-e-Sharif Mosque) with a large park around it. Access to the interior is forbidden to non-believers. Renovation, which has been underway for several years, is progressing. A new wing with minarets is currently being added to the west. The walls of the gates to the park at the cardinal points are also being re-tiled. It is pretty much the only sight in a noisy, dusty and, as everywhere in Afghanistan, very dirty city, which is contributed to by unfiltered car exhaust fumes and open coal fires everywhere.

My accommodation was right by the south exit; for 500 Afghanis I got a room with satellite TV (thank goodness for Test cricket!) and a communal outhouse that could at least be locked and even had running water from the tap.

The new Balkh Provincial Hospital was built in 2011 using German, Japanese and Swedish tax payer’s money. So far, decay has been limited. The Americans then bombed the hospital in 2015, killing 30 people, including 13 doctors and at least nine patients.7 The German Consulate General on Darwaz-e-Balkh, formerly the site of the Mazar Hotel, is considerably uglier. No legal or consular services – only emergency aid. No visas are issued.

They clearly have something to hide, since they are clearly not engaged in consular activities. The Consul General is also the head of the multinational SCR staff (SCR = “NATO Senior Civilian Representative;“ Quotes from von: http://www.kabul.diplo.de/. The German Foreign Office then wrote on its travel warning website in June 2021:

A security guard, by the way, scolded me for taking photos. After I explained to him that my taxes had clearly been wasted here, he relented.Attacks on the German Consulate General in Mazar-e Sharif in November 2016 and in front of the German Embassy in May 2017 severely damaged both missions, so that they are closed to visitors. Legal and consular matters such as passport and visa issuance cannot be handled in either Mazar-e Sharif or Kabul.

It is deliberately omitted that there was never any public traffic in Mazar-e Sharif.) of the Regional Command North in Camp Marmal.

It’s striking that while information about every donated kindergarten chair can be found quickly online, there’s nothing about this cubicle, apart from the foreign secretaries Westerwelle inauguration trip in 2013. I’ll have to dig further into that. The place was taken over from the Americans, who spent US$ 80 million between 2009 and 2012 instead of the originally planned US$ 26 million, only to then discover that the situation didn’t meet their standards of security. (“American officials say they have abandoned their plans, deeming the location for the proposed compound too dangerous.” Von: https://web.archive.org/web/20230205073924/https://diplopundit.net/2012/05/06/us-consulate-mazar-e-sharif-80-million-and-wishful-thinking-down-the-drain-and-not-a-brake-too-soon/ und https://diplopundit.net/tag/consulate-mazar-e-sharif/) The first question that arises is: Are German security standards for staff protection lower than those of the Americans? Was the place, the land was only leased from the Americans for an eleven-year period, perhaps given to them as a gift?

On the second day, I was approached on the street by an English teacher who first dragged me along to the private school where he taught. In the mornings, he worked in the administration of a shipping company. In the manager’s office, I was shown around as a curiosity. A bearded, elderly Afghan, “leathery“ type, was there. When I was asked to guess his age, I tried to be polite and said “60,” although he looked considerably older. In fact, he was 48! 35 years of war have certainly taken their toll.

Finally, I was invited home for dinner. Before the meal was served, the father, or rather the patriarch, made an appearance. Clearly a figure of respect, he exuded natural authority. I was invited to be a guest at his house anytime, followed by a five-minute thank-you speech, for Germany having “given Afghanistan a government” at the Petersberg meeting. Otherwise, thanks to “Mrs. Merkel,” who sent her soldiers to support the Americans. “We admire strong Germany” – wouldn’t it have been better if we Germans had won the war? Then the British and Americans wouldn’t have come here in the first place, etc. “What a pity, Hitler was a good man,” etc. I then gave him my Führer portrait as a souvenir. A dignified by father … A total of four brothers showed up, the eldest having been a guard at the camp for eight years. He was disappointed that his request to be taken to Germany as an asylum seeker had been rejected. Towards the end of the evening, it became clear to me why – he gave me a 1½-hour lecture on the intricacies of Imam Ali’s life story, which was eagerly interpreted by his brother but extremely tiring. If he had done the same with the two German officers who had visited the family earlier, he was lucky to still have the job. In any case, I would have marked his file as “suspected Islamist.” The youngest of the four brothers, somewhat hard of hearing, was clearly the most intelligent. Why anyone would even bring in such unqualified personnel as camp guards is beyond me. Those Afghan guards let themselves as mercenaries for good money, fully aware of the risk they were taking, but voluntarily and without coercion. Even Afghans must be expected to show a certain degree of personal responsibility. If they were motivated by greed, they must tolerate a neighbor who, out of envy, throws a hand grenade into their yard, because they were undoubtedly aware from the start that such things could happen (throwing hand grenades is a local custom, “I just have to tolerate it,” right?). In any case, in this male-dominated society based on deceit and selfishness (“Thanks to Allah!”), gratitude for the fact that the position enabled them to support their oversized family – which, due to a lack of birth control – is unlikely to be expected.

Kunduz: Frontline City!

The political stupidity of the German mission in Afghanistan could not be better portrayed than by that picture taken satirical magazine Titanic. [The German „Frontstadt“ has stronger connotations than “Frontline City” tending more towards “to the last bullett.”] After the American occupiers decided in the spring of 2021 to abandon the puppet government they had installed and withdraw their troops from the country (which did not prevent the Air Force from continuing to bomb from outside), Kunduz was liberated from the indigenous Taliban on August 8, 2021, after several days of encirclement. (SZ 8. Aug. 2010: „Taliban erobern Kundus: ,Die Stadt sei am Sonntag nach heftigen Kämpfen gefallen, […] Auch mehrere wichtige Regierungsgebäude sind offenbar erobert worden. Die Regierungssoldaten hätten weiterhin den Flughafen und ihren eigenen Stützpunkt unter Kontrolle, […] Die letzten Bundeswehr-Soldaten wurden am 30. Juni nach fast 20 Jahren abgezogen. […] Kundus, das seit langem von Taliban-Kämpfern belagert wurde, gilt als strategisch wichtig, weil es am Zugang zu den an Rohstoffen reichen Provinzen im Norden des Landes und in Zentralasien liegt.'“ (https://web.archive.org/web/20210808105933/https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/afghanistan-taliban-erobern-kundus-1.5376283) und NY Times, schon am 3. Aug: “U.S. Airstrikes in Afghanistan Could Be a Sign of What Comes Next. American forces have stepped up a bombing campaign […] But the dozens of airstrikes, which began two weeks ago [ca. 18. Jul.] as the Taliban pushed their front lines deep into urban areas, […] Beginning next month, the president has said, the United States will engage militarily in Afghanistan only for counterterrorism reasons, to prevent the country from becoming a launchpad for attacks against the West. […] But helping Afghan partners fight for their lives is the point of the stepped-up bombing campaign, military officials said. […] Kabul, where the United States maintains an embassy, with some 4,000 [!] people.” (https://web.archive.org/web/20210804005928/https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/03/us/politics/us-airstrikes-afghanistan.html)

After a good five hours in a shared taxi, I arrived in Kunduz. This is where “Germany was defended“ in the Hindu Kush for the past ten years. 56 soldiers died a hero’s death for the Fatherland; there is was a memorial in the camp in Kunduz. [The Air Force had enough space to fly out the stone, which weighed several tons.  At the same time several hundred of its Afghan helpers were left stranded at Kabul airport because they didn’t have the coronavirus vaccination, while the Taliban (at that time still a “terrorist organization“ according to the Foreign Ministry) screamed at the airport gates for the heads of those trying to flee.] In Mazar I was told that a) the people in Kunduz were “weird” and b) “security is very bad.” I did avoid going out at night, but the people seemed to be leading normal lives, so the situation couldn’t be that bad.

At the same time several hundred of its Afghan helpers were left stranded at Kabul airport because they didn’t have the coronavirus vaccination, while the Taliban (at that time still a “terrorist organization“ according to the Foreign Ministry) screamed at the airport gates for the heads of those trying to flee.] In Mazar I was told that a) the people in Kunduz were “weird” and b) “security is very bad.” I did avoid going out at night, but the people seemed to be leading normal lives, so the situation couldn’t be that bad.

Unfortunately, I missed the Taliban attack on the public prosecutor’s office on October 27th, which left eight dead and ten injured. We drove past the High Court two hours early , even though I would have loved to have sold exclusive photos to the Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ). The first place I stayed at was about 200 meters from the scene and no one in the bazaar heard the gunfire or interrupted their business (youtube-Video). I only found out about it the next morning when a security guard, who happened to be related to my hotel landlord, approached me on the street and wanted to tell me something, but couldn’t because we didn’t speak a common language. It was only when we met again by chance ten minutes later in the lobby that someone interpreted. I was told three days later that he had called again, worried and asked if I was perhaps mentally ill because I was walking around the city alone during the day.

Allegedly, 1,700 people visited Afghanistan in 2013.

Years of visitors on official missions, with fat expense accounts, have left the city’s hoteliers complacent and expensive. As of October 2014, the accommodations offered are about one-third to one-half overpriced for the quality offered. As with many merchants, they often lack a realistic understanding of the purchasing power of a dollar and, even more so, the awareness that good money also requires good service.

The Ariana Hotel & Wedding Hall, which is praised in the most popular travel guide, turned out to be a complete disaster – and has further reinforced my disdain for LP. For US$20 (non-negotiable), you can get rooms above the aforementioned banquet hall. They’re noisy, some without windows. The rooms are completely unkempt; even after a change of guests, they’re only cleaned upon request and even then, clean sheets aren’t available. I can’t remember the last time I asked for a room to be cleaned in a hotel. The sanitary facilities are typically unkempt. The hot water boiler and TV are non-functioning accessories. Hot water, even in buckets, isn’t available. Completely inadequate value for money. When I then asked for the light in the bathroom that evening - even a blind person could see that the problem wasn’t the bulb, but the light switch hanging from the wall - I was told that after twenty minutes of pretending to change the light bulb, I would just have to shit without light [Luckily I am skilled enough to find my bottom in the dark]. When the boss asked me again: “If you don’t like it here, you can always go somewhere else.” Which I did the next morning, forgetting to pay without any remorse.

I then moved one street away to the “Haji Torabaz Khan Guest House” (formerly: “7 Days GH”). The charge is a hefty US$ 50 per person, negotiable to 2,000 Afghani per day. That’s the monthly income of a farmworker. Under German management until 2009, but since then significantly run down by third party operators, the family that owns the place is striving to improve again. Large rooms with clean bathrooms that even have lukewarm water. Some rooms offer satellite TV (only oriental channels). The inner courtyard contains what is probably the only patch of manicured lawn in town. A pool, begun in 2007, was never completed. The place is far from perfect. You can get significantly better amenities for less money at any guesthouse in the Bavarian countryside.

Staff were helpful and spoke reasonable English. A nephew of the owner, who, after growing up in Norway speaking good English, married his cousin and now lived in Kunduz. I learned a bit about the family background. However, he was a comparatively strict believer in the Koran: “Our religion, which we love more than our families …” He seemed to like my attitude that I couldn’t care less whether I was shot by a Taliban or run over by a truck (the latter is significantly more likely in Afghanistan!). One evening we had a long conversation about kismet, the Muslim concept that a person’s fate is predetermined. From this he deduced, for example, that it would be perfectly fine for a family to have seven or nine children, none of whom they are able to feed, so they are sent to beg or shine shoes at the age of four or six. That was the “kismet” of these children, not their parents' fault. An uncle then remarked that he hoped my only son would provide for me at my age – the concept of a solidarity-based social security system was incomprehensible to him. Two other visitors then presented me with a bilingual Koran. I then left this extra 800 grams of luggage with the American Jew in Dushanbé.

The receptionist was greatly amused when I told him I’d been to the barber. That was so strange, because the Western liberators who had protected Kunduz for ten years apparently never got out of their armour-plated vehicles to take a stroll around the bazaar. One does not win “hearts and minds” that way. Even the few remaining UNMOG officers still stationed in Kunduz are only seen driving around in their big SUVs.

When I originally planned the trip, the road to Faizabad and from there to Khorog or Ishkarshim in Tajikistan actually looked quite good on the map. From there, travelling along the Pamir Highway would certainly have been nice. As a spoiled European, I had overlooked the fact that a “road” leading through the mountains of Afghanistan is not necessarily passable or even used after the end of September. So, the GBAO permit (Required to travel the mountainous Gorno-Badakhshan region of Tajikistan – 45 % of country’s area, but only 2 % of the population.) had been applied proved unnecessary. Instead, we headed straight for Dushanbé in Tajikistan.

Shir Khan Bandir border crossing

I have described the procedures on German wikivoyage detailled as Grenzübergang Shir Khan Bandar/Panji Poyon. I have to elaborate a bit on: Before entering Tajikistan, it is essential to check whether your date-specific visa is already valid for the day of entry. Arriving early will result in rejection or, if you arrive the evening before, hours of sitting in no-man's-land.

After a week in Afghanistan, I’d truly had enough, especially since Kunduz, with its filth, unfriendly people and expensive hotels, offered nothing but the bazaar to wander around. So I deliberately drove to the border on October 31st, even though I knew my visa wasn’t valid until November 1st. The town itself is considered a “port,” because until the bridge opened a few years ago—paid for with US$ 37 million by the American taxpayer – ferries crossed the river.

After recovering from the shock of seeing a white foreigner passing by without a diplomatic passport at the Afghan customs post, I was dutifully invited inside to have my luggage “inspected.” I was asked to unfasten the clip on my backpack, then close it again two seconds later! “Have a nice day.” At passport control, one local waited in front of me. Exiting the country took as long as it took the border guard to write my personal details (father’s religion?) in a thick ledger. With the new surname „Deutsch” [“German”] entered therein, I officially left Afghanistan.

Tadjikistan: Dushanbé and Khujand

Exchange rate: 1 € = 6,8–7 Somomi (divided in 100 Dirham) [June 2021: 1 € = 13,5 Somoni, May 2025: = 11,3 Somoni].

On the other side, the second border guard noticed that my visa wasn’t valid until the following day. His colleague had already waved me through (the usual “Minchen? FC Bayern; Mercedes; Gitler – good.”) A lengthy palaver ensued until they decided to call the “komandir,” who soon arrived. More palaver. An Afghan man told me in English that they had already decided to let me in, but first they had to put on a bit of a show.

Tajik customs and border control still operates meticulously, following the Soviet model. Locals are “allowed” to expedite processing by shoving banknotes relatively openly across the table. The fee is 20 Sonomi (€ 3) for a passport stamp and 40-50 Sonomi for the customs officers, depending on the amount of goods brought. No bribes are demanded from Western foreigners. Luggage is routinely x-rayed and searched. Cash amounts in international currencies must be declared verbally. Most travellers must empty their pockets in the back room. The rest of their luggage should never be left unattended in the anteroom, as thefts by staff are said to be common. Upon entry, you will receive an additional form, which must be retained until departure.

After I’d packed up again, I was escorted under guard to a fenced-off area to the major’s office with another officer. We drank tea, he called a relative who spoke English who interpreted over the phone, back and forth, more tea, another phone call, even more tea, brought by a young recruit. At some point, a border guard brought my passport, which was placed in front of the major and left there for a while, because there was more tea to drink. After another round of telephone interpretation, interrupted by another cup of tea, I was told: “Welcome to Tajikistan.” Six hours earlier than allowed. (The stamp in the passport, however, is suspiciously faint.)

The major then escorted me out. Turning to the young recruit, he said something like, “Soldier! Carry this man’s backpack!” He then did so to the gate. Untying my pack for another soldier who had taken over, a minibus that was just passing was stopped. Civilians are not allowed to walk anywhere in the border area. After a friendly farewell from the major as I boarded the minibus, we drove the two hundred meters to the shared taxi stand. The bus driver, who brazenly demanded 5 sonomi from two other passengers, was apparently uneasy. I got the ride for free.

The two Afghans on the bus, one a former UN employee who had previously been stationed in Mali, immediately arranged to share a ride with me to Dushanbé and negotiated a fair US$ 60 for the driver to our door. We were driven in a well-maintained black Mercedes 190 with 350,000 km on the clock. The driver then tried the “increased fare” trick with me when I got out, apparently because the rate of the somoni had dropped rapidly …

I also changed my already vague plans for the trip to Tajikistan, this time due to weather conditions. See my route map under Possible Plans in the Pamirs, where various routes from Kunduz via Faizabad along the Pamir Highway to Osh in Kyrgyzstan are indicated – it certainly is a “high way” in the truest sense of the word given the altitudes. The route goes through the high mountain region of Badakhan (GBAO for short). This region comprises 45 % of the country’s territory but only three percent of the country’s population. Not only foreigners require a special permit; Tajiks are also only allowed to enter the region, which is predominantly inhabited by Ismaili Muslims (Ismaelites are a Muslim sect that exists without mosques or imams. They worship their spiritual leader, the Aga Khan, like a god and give him a significant portion of their income. Recognized by the English as an Indian prince, these gentlemen have lived lavishly in Europe for several generations as part of the jet set, as readers of those “yellow press” that have been available in doctors' waiting rooms since the 1960s will be familiar with, specially thanks to the “Begum“ (Yvette Labrousse 1906–2000, gefolgt von Gabriele Renate Homey *1963, alias Gabriele Thyssen, alias Begum Aga Khan, alias Gabriele Prinzessin zu Leiningen). Every now and then, a few crumbs fall to the faithful. They provide famine relief in the region, subsidize hospitals and schools and talk loudly about it, as befits charity.) and suffered from acute famine in the late 1990s. This stamp is available free of charge in Europe upon application for a visa; in Central Asia (e. g., Bishkek), the fee is US$ 90, although there is no guarantee of success. Applying in Dushanbe is said to be even more complicated. If you look online, you’ll find numerous blogs by extreme cyclists who are tackling this gravel road at 3,000-4,000 meters.

I've been told that the shortest route, through magnificent scenery, from Kunduz via Faizabad to Khorog can be snowy from the end of September and I would probably have had to hire a jeep for US$ 300-400 on my own. Alternatively, you could have reached the border town of Ishkarshim in the very south of Tajikistan from Faizabad; this route is also snowed unter from October onwards and is probably only accessible by private car. In Tajikistan, there is only one bus per week on this route, so I would probably have had to try hitchhiking for the 3-4 days to Osh. Not an encouraging prospect in early winter at 3,000+ meters with the corresponding nighttime temperatures.

The route through the Tajik Kulyab, although probably still snow-free up to Khorog, would also have required a private car.

Dushanbé

Pronunciation note: The name of the capital, Dushanbé (Душанбе), is accented on the final e. The “dj” in the country’s name denotes the voiced alveolar fricative (ʑ).

Former world’s tallest flagpole, Somomi monument, new presidential palace and eagle in Dushanbé’s central park.

Former world’s tallest flagpole, Somomi monument, new presidential palace and eagle in Dushanbé’s central park.The population’s customs and traditions clearly reflect the migrant element that came from rural areas during the civil war, replacing the Russian-born intelligentsia who fled. One ironclad rule in traffic is: Do not brake for pedestrians! Otherwise, traffic lights and speed limits are merely recommendations. You’ll be regularly flagged down by the traffic police anyway and you’ll be fined an average of 20 Son. for “violations” in cash and without a receipt.

Practically all of the tourist attractions are located around the central north-south axis, Rudaki Prospekt, south of the former Chum department store. My couchsurfing host also lived very close by. I really shouldn’t say anything bad, since he put me up for three days, so I’ll just say this: “God created a large zoo and everything in it,” D. is a Jewboy from New York, two facts he loudly announces. As an employee of the American Chamber of Commerce, he is a very much the Unpleasant American. He is also a racist, full of contempt for the people among whom he has lived for seven years. An unkempt figure who spends his weekends watching American college football in front of the TV, he is simultaneously too lazy to change a lightbulb – he calls the janitor for that. I had the “pleasure” of overhearing two phone calls with his secretary – I couldn’t stand two days with such an obnoxious boss from hell. (A side note: I am fully aware that for reasons of “political correctness” it is strictly forbidden to say even a single negative word about persons of the Chosen People who control God’s Own Country, all of them are by nature perfect and inapproachable … I have therefore been extremely polite in my description above.) I was happy to give him the bilingual Koran from Kunduz for further learning about cultural differences.

I was only able to stroll through the relatively compact city of Dushanbé on the first day. From day two onward, it poured with rain plus the “döner kebab of death” took effect. The evening before, I met up with C., a German development worker who has been trying to establish a real estate financing system in the country for several months. At the expat bar Public Pub, I tried the “local wheat beer” (as mentioned on the menu), which tastes like a very sour Pilsner.

You can get to Khujand (Хуҷанд) from the Cemzavod Avtovokzal (“Cement Factory Bus Station”) at the end of a trolleybus line at the north end of Rudaki Ave. Pumped full of charcoal tablets (I couldn’t stomach much after two days of “Delhi belly”), I let an Opel Vectra driver hijack me for a reasonable price, not considering that in weather like this in early November, Bayern 3 [A Bavarian radio station] would likely announce bsnow at higher altitudes” on their traffic report. On top of that, a Vectra has front-wheel drive and my driver only had summer tires. At some point, we ended up pushing the car up the hill until a snowplow came along. At least I learned two more Russian words from my fellow passengers along the way: 1) “prrroblèm” in view of the blanket of snow and 2) at the toll booths: “Schlagbaum” (barrier) – Russian isn’t that difficult after all! After all, the route, upgraded by a Chinese company and operated for several years in exchange for tolls, was in a condition one would expect from a state highway in the far reaches of the Bavarian Forest. It takes you through some very wild, long and unlit tunnels in a very remote mountainous region. In one village, I saw a sign for the “Welthungerhilfe“ [a German charity] base.

Khujand

After an hour of wandering around, I ended up at the “Shark Hotel,” recommended by the region’s only international travel guide, in the green and yellow building of the same name near the bazaar, recognizable by the 1954 Lenin/Stalin medallion on the facade. There’s no signage, but the bed costs 15 Son. (US$ 3). You very literally get what you pay for: a shared restroom with three pit toilets but no doors doors and no running water. Ancient beds and unwashed sheets, which fortunately you can’t tell given the dim light in the room. I treated myself to the “luxury” of booking a three-bed room for myself. At least I got a room key. To shower, you have to use the facilities in the bazaar’s public restroom (8:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m., 5 Son.). A gentleman keeps quiet about their condition, but at least the running water was warm. The owner of the “hotel” speaks rudimentary English but can’t provide any information about his hometown. While he chatted at me, he nibbled incessantly on moldy white bread. The beds turned out to be so sagging and short that I voluntarily slept on the floor that night. Maybe I'm just getting old, but I do have certain expectations regarding the quality of accommodation these days … As of June 2025 Мехмонхонаи Шарқ is still listed on google maps

After I had found out at the station far out of town that there were no trains to Kyrgyzstan, I decided to bite the bullet and next morning to again:

Transit through Uzbekistan

I first took a marshrutka the sixty kilometers to Kanibodam, then from the bus station there continued to the border. Due to Uzbek harassment – Tajikistan is even less known for being “Islamic” than its other neighbors – the border is closed to car traffic (I can’t confirm whether this also applies to foreign vehicles) and otherwise, not much happens.

First, I had to stand around outside the Tajik post for half an hour before I was even allowed to set foot on the sacred ground of the border crossing. Customs was uninterested in me. The border guard, in a cubbyhole with a sticker informing me that it was financed with EU tax money, spent a good ten minutes typing the data into the computer using my passport in the one-finger search system. Now, I hadn’t bothered to register with the KGB (now called OVIR) in Dushanbe within the required three days. While this is no longer required for tourists staying for up to 30 days, this exemption seems to only apply to tour groups, not to “private trips.” The young border guard only noticed the missing piece of paper after he had already stamped me out. A convincing “Touristy, registratio njet!” was enough to intimidate him.

On the Uzbek side, where I've heard that customs officers sometimes take three hours to look through all the images on a laptop, I was first greeted by the ”feldscher” – another lovely Russian word from the pre-modern German word for “military surgeon” – to take my temperature because of Ebola and such …

On to customs, where, surprisingly, the form, which had to be filled out twice, was even available in English upon request. In the small hut heated by a wood-burning stove, a large plasma screen was playing an Uzbek soap opera at full volume. The customs officer handling it, who spoke good English, finished the form in two minutes. The usual conversation with the men followed: “From Minschen? – Ah, FC Bayern,” then “BMW,” “Mercedes gutt,” and “Mrs. Merkel“ … The usual counting out of my cash was omitted. I did have to unpack half of my backpack and was asked for a “notebook” – I pulled out my pocket diary, clearly a “notebook.” After the pun was cleared up with mutual laughter, I could pack up again – I didn’t need to show the photos from my cell phone and despite having a beard I was not judged to be an Islamist either. The whole process took less than five minutes.

I waited a little longer at the passport counter. Not only because we were typing in the one-finger-system again, but also because the power went off and three Uzbeks needed half an hour to find the fuse which is clearly visible on the wall at the back and then press it back in …

We then went to the next village in a minibus whose driver didn’t want Tajik somomi. The price for the locals was 2000 Uzbek som. He first asked me for 3000, but when I saw my small dollar bills and cheekily reached for the fiver (15,500 S.), the scene quickly became unpleasant, so I gave him US$ 2 just to get rid of him. Meanwhile, I was surrounded by the black-market money changers outside the bazaar – it’s always astonishing how hectic people who usually just stand around idly all day can suddenly be. When converting from somomi to euros to som, I made a mistake and ripped myself off by 20 %. No matter, it wasn’t much. Armed with 65,000 Som in 500-Som notes, a guy drove me briskly fifty kilometers to Kokand for a reasonable 15,000 Som. From there, in a shared taxi, with the aforementioned only decent taxi driver I met in six weeks, I drove ninety kilometers to Namagan for 4,000 Som (in the front seat!). He not only dropped me off at the correct departure point, but then negotiated properly with the connecting driver to Uchkurgon, the last town before the Kyrgyz border near Shamaldy-Say. A marshrutka with two drunken Russians took me to the crossing. They were so enthusiastic about the foreigner that they not only paid for the ride but also wanted to take photos.

By now, it had gotten dark. I entered the Uzbek border post through a large gate after an preliminary passport check. There were maybe ten or fifteen people in the waiting room with me. I was asked if I, as a German, had a bicycle with me – no other compatriots had been seen at this post yet. First, the customs check began – a horribly meticulous woman in front of whom I stood in line. She found 3,000 undeclared Belarusian rubles on the man in front of me – pennies. She led him away amid a lot of shouting and huffing. Bang, another power outage. After three-quarters of an hour in the dark, the others waited outside, electric light and the border guards returned. I quickly went to their cubicle, second in line. The copper at the counter was amazed that it was possible to get from one border crossing to the other in just six hours. Stamped out – the customs officer hadn’t reappeared yet. I, too, had not declared a small amount of change on my form, so I hurried through the back door into the courtyard, where a soldier checked my passport once more. He opened another large gate, and I was in Kyrgyzstan.